A Yooper Ski Jumping Legacy

A Personal Memoir of Ski Jumping in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

A firsthand account of ski jumping in the Gogebic Range area of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula during the 1970s and early 1980s.

A personal memoir of ski jumping experiences in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

About This Book

This is a firsthand account of ski jumping in the Gogebic Range area of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula during the 1970s and early 1980s. It weaves together personal experiences with the broader history of a sport that once captivated communities across the northern United States and is primed to captivate the world once again!

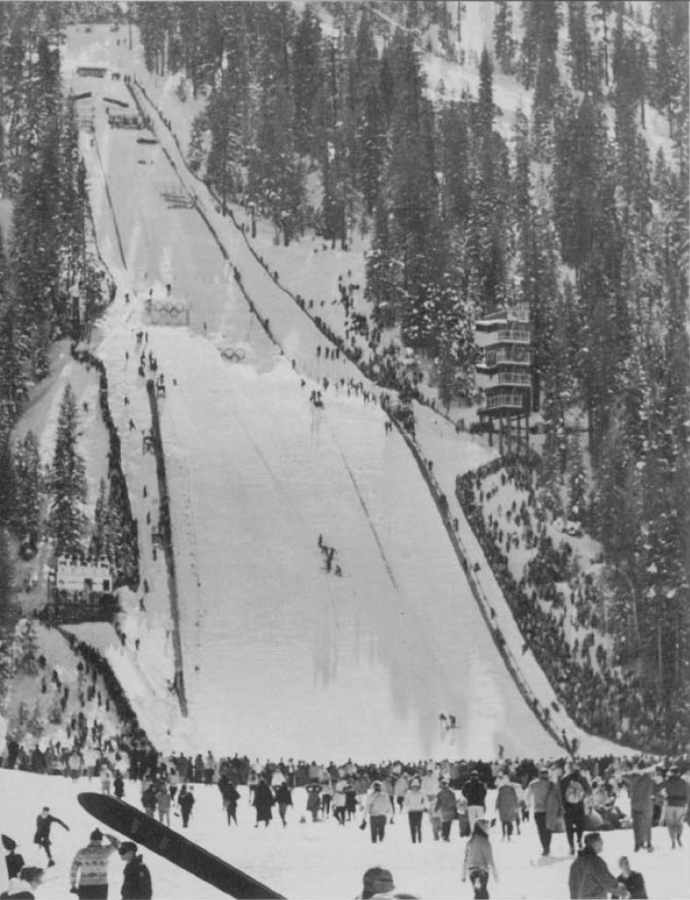

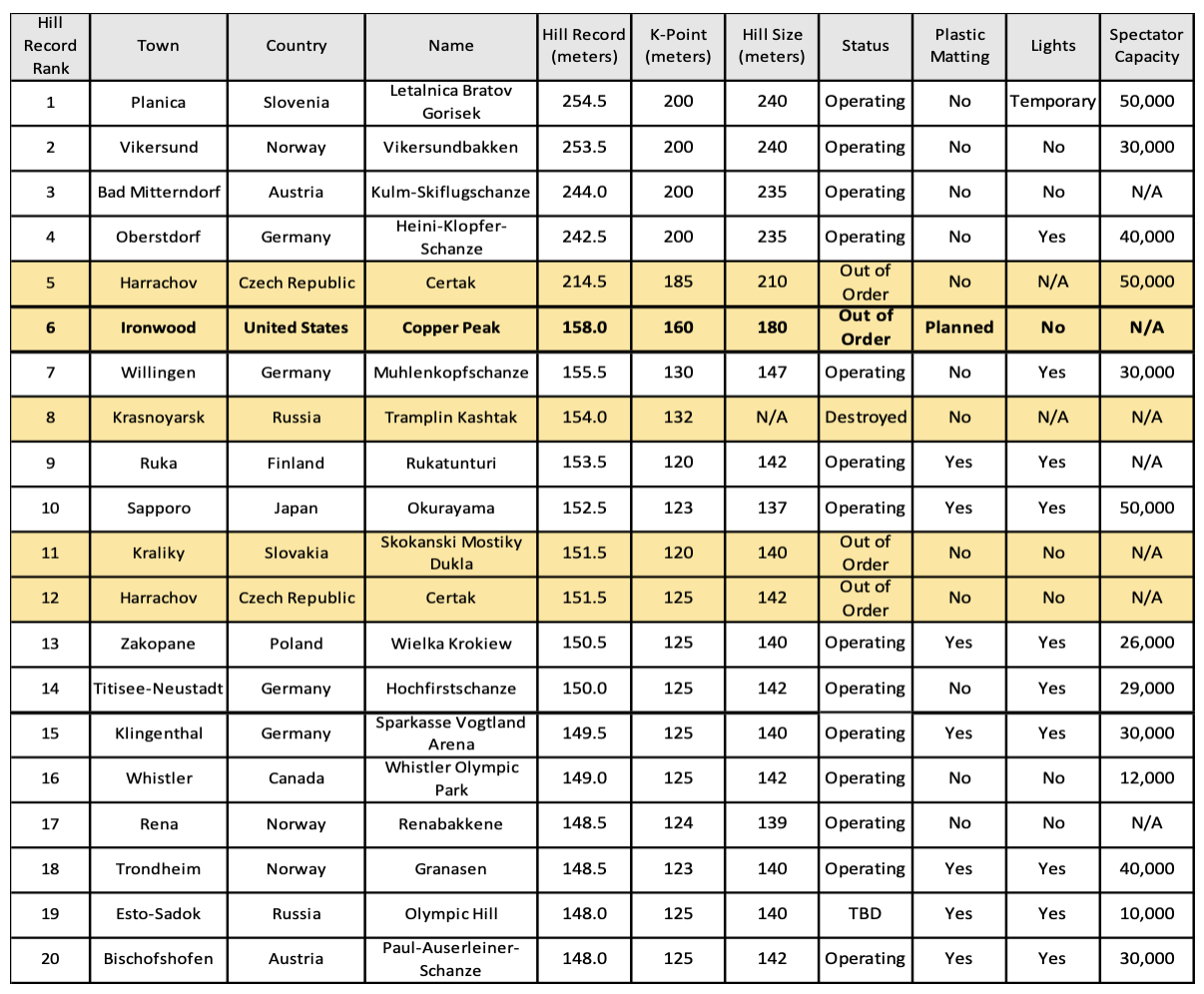

From the small 30-meter Iron Bowl to the towering 90-meter hills at Pine Mountain and Westby, and the legendary ski flying facility at Copper Peak, this memoir captures the thrills, challenges, and camaraderie of competitive ski jumping.

What You’ll Discover

- Family Legacy: Savonen family roots in ski jumping and the Upper Peninsula

- Local Hills: Anecdotes from the Iron Bowl and Wolverine ski jumps in Ironwood, Michigan

- The Competitive Circuit: Experiences on the Midwest tournament circuit from the U.P. to Wisconsin and Minnesota

- Big Hill Dreams: Riding the 90-meter hills at Pine Mountain and Westby, and competing at the Junior Nationals

- The Sport’s Future: Reflections on preserving and growing ski jumping in America

1 - Introduction

1.1 – Foreword

Ski jumping holds a special place in the hearts of Yoopers and European heritage alike. As sketched here, the experiences of a junior class ski jumper in the 1970’s Ironwood, Michigan area should resonate with other ski jumpers, especially from that era. For those engaged in ski jumping after the 70’s era, may it trigger an ‘aha’ moment.

For my family, this memoir provides an additional perspective of our Dad (or Grampa or Great Grampa) whom they didn’t have the opportunity to really get to know. Also, this account pays homage to the many that steadfastly and sacrificially supported this sport, especially during the 70’s and 80’s time period, led by those of the so-named ‘The Greatest Generation’, and their successors, the ‘Silent Generation’.

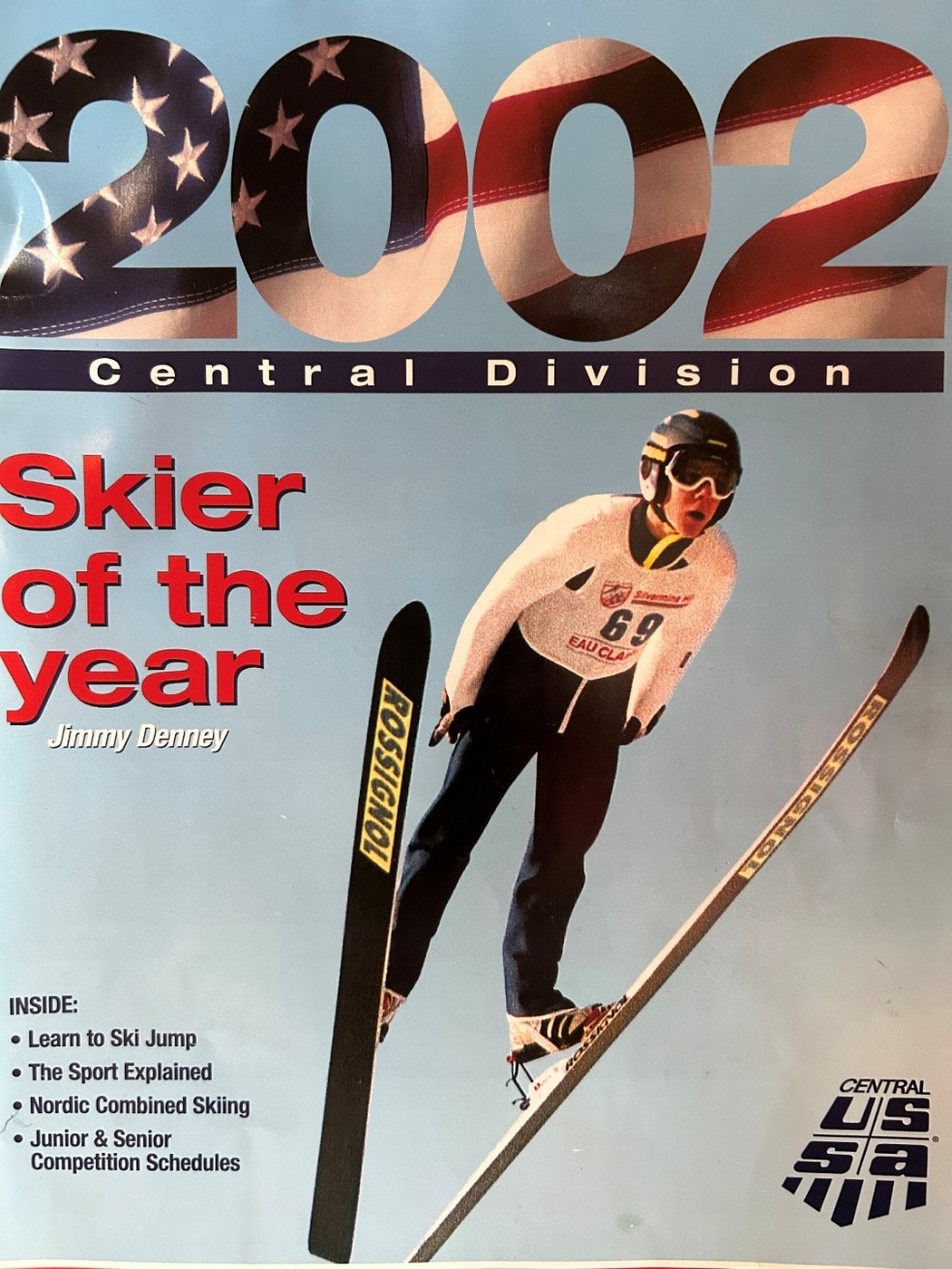

In the latter pages, a few personal viewpoints are expressed on the evolution and future of ski jumping. Retiring from ski jumping over four decades ago, it provides a ‘Rip Van Winkle’ perspective to compare and contrast ski jumping for the 50 years difference between the 1970’s and today. I also promote how participation could be expanded on a broader scale. A few of the progressive U.S. ski jumping organizations are mentioned that have adopted a promising, multi-faceted model.

I trust that this journal does not exhibit symptoms of the Lake Wobegone Effect. What is the Lake Wobegone Effect, you ask? Stemming from Garrison Keillor’s fictional small town of Lake Wobegone “where all children are above average”, it is the narcissistic tendency to overestimate one’s own accomplishments, despite what is found in documented history.

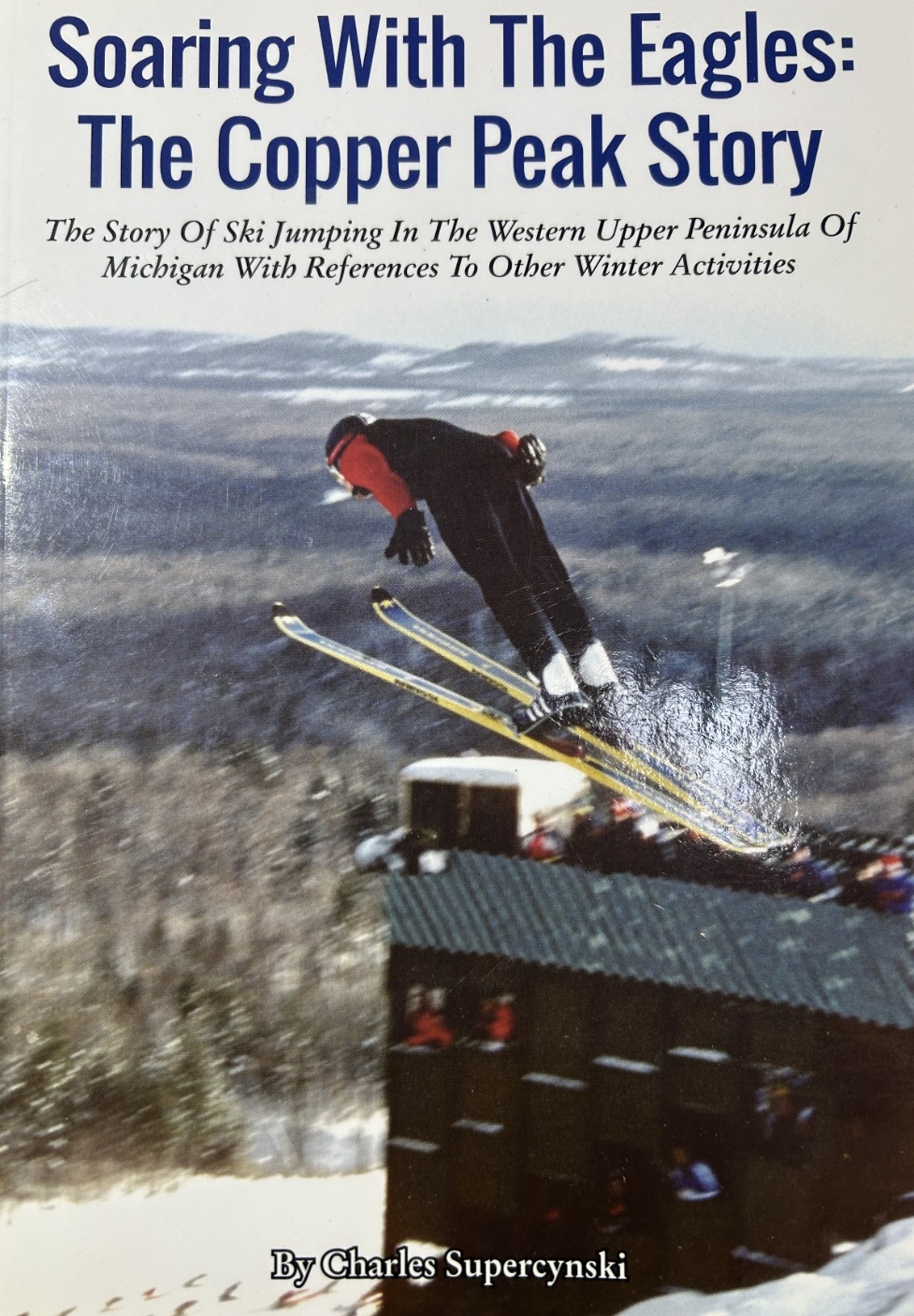

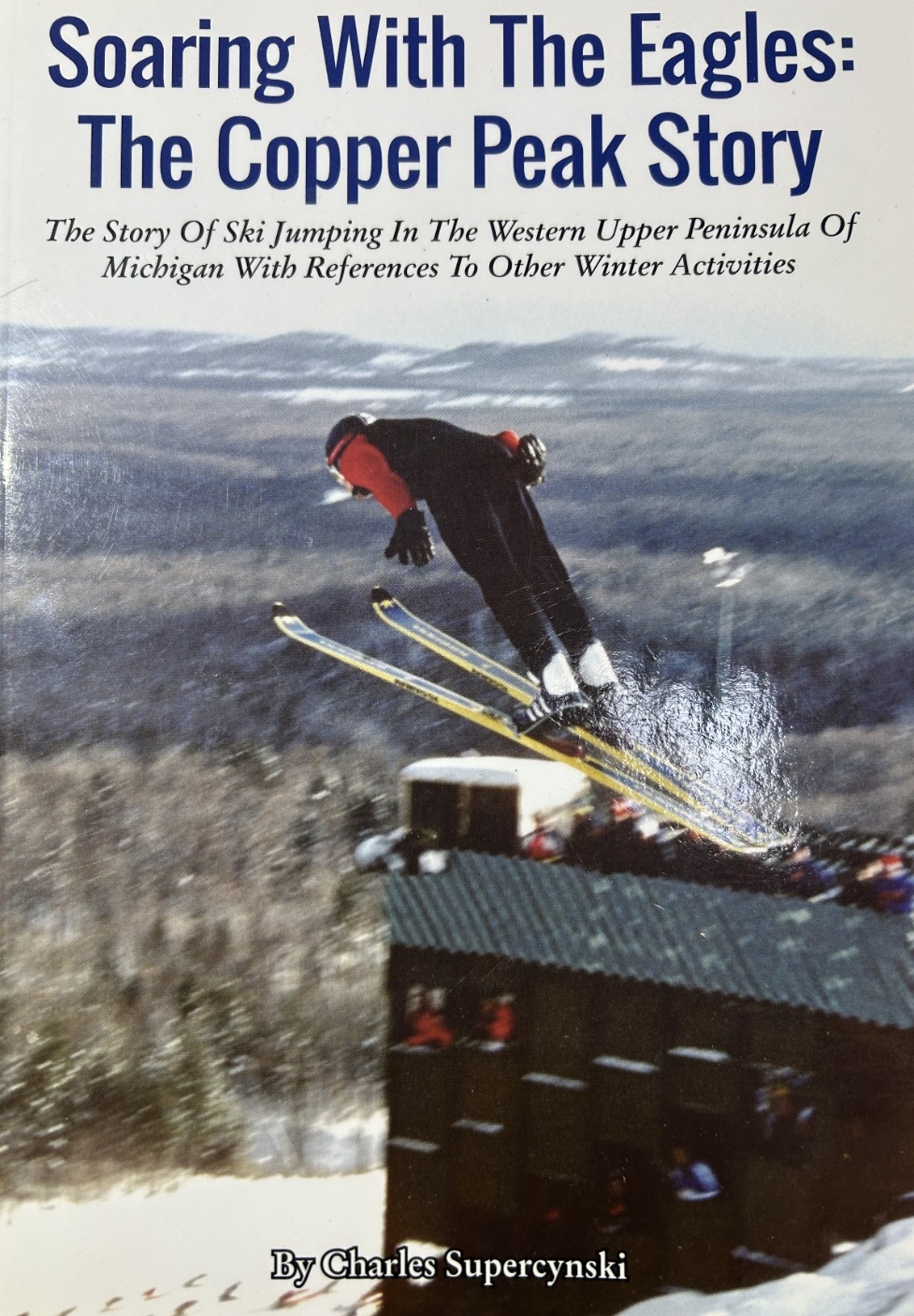

This memoir does not pretend to be a comprehensive review of the sport of ski jumping. To color in the long history of ski jumping in the upper Midwest and specifically, the Gogebic Range of Michigan’s western Upper Peninsula, I’d point you to Charlie Supercynski’s ‘Soaring With the Eagles’ (1) as an engaging and thorough account. It was an invaluable resource for U.P. ski jumping history, while weaving my personal story and anecdotes. Several perspectives expressed in these pages parallel that of Charlie, even though he and I traveled different paths over the years.

Past and present ski jumping generations are increasingly recognizing the value of creating archives and historical accounts of this wonderful sport. There are several books and electronic caches containing the history and culture of ski jumping that can be discovered with a bit of internet searching. Understandably, such publications usually focus on a particular region. Further appreciation of the long history of skiing can be gained by venturing to the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame in Ishpeming.

For other personal recollections, an outpouring of anecdotes and remembrances are accumulating in the US Ski Jumping Story Project. Heartwarming insights and greater appreciation of what it takes to be a ski jumper are shared. It illuminates how much others have given to, or have gained from, the sport. Many others have participated in ski jumping longer than my relatively short fourteen year stint, so there must still be a treasure trove of stories waiting to be revealed.

Besides the title, the word Yooper is periodically exercised in this journal. Surprisingly, not all Michiganders (not Michiganians!) know that a Yooper is someone born (or in a less pure definition, resides) in the Upper Peninsula (aka U.P.) of Michigan. Broad use of the word Yooper is not that ancient. Its original publication was as late as August 5, 1979 when the Escanaba Daily Press hosted a public competition to propose a word to best refer to the U.P. people. It can be found today in the Merriam-Webster dictionary.

Unless otherwise noted or obvious in context, several words are used interchangeably, such as ski jumper, jumper, or skier and hill, jump, or ski jump.

Several American cultural references from the 70’s and 80’s are sprinkled into the text. For those born after those decades, a follow-up with your favorite electronic device may arm you for your next trivia night.

1.2 – Heroes of Yore

Across the span of sports in which I have participated, ski jumping was by far the most fulfilling. In the late 1990’s, nearly 20 years after my last jump, I would still literally dream about gliding through the air to the bottom of the jumping hill.

I find that a majority of sports minded youngsters typically adopt their favorite sport, team, and athlete(s) sometime during the ages of 9 - 11. As a young left-handed baseball player, I tried to emulate Norm Cash and Mickey Lolich. I debated with a wayward thinking cousin who adamantly claimed that Denny McLain was better than Mickey. McClain was just coming off two monster Cy Young years (31 wins in 1968 and 24 wins in 1969), yet he only won another 21 games over the rest of his career, plagued by arm injuries and self-induced trouble. Meanwhile, the rubber armed Mickey was the 1968 three-game winning World Series hero who sustained success deep into the 70’s, thus settling that debate conclusively.

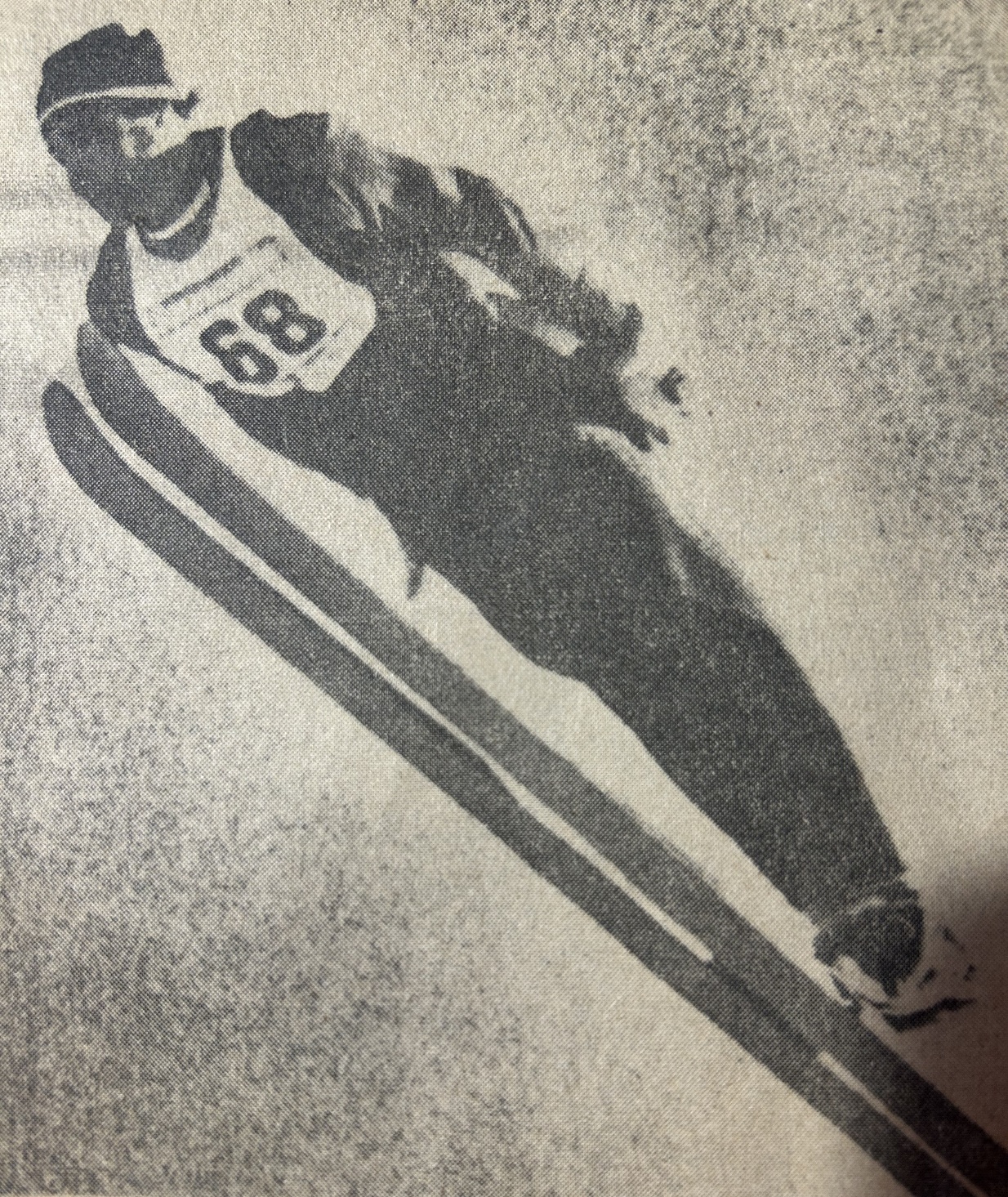

In ski jumping, Jerry Martin was the hero of the time. He was at the pinnacle of his achievements in the early to mid-70’s. A personable and stylish jumper, Olympian in 1972 and 1976, and U.S. national ski jumping champion in 1971, 1973, and 1975, we witnessed his triumphs at the local Copper Peak ski flying hill. He sandwiched 1st places in 1973 and 1975 around a 2nd place in 1974, while extending the hill record each year. On his way to the 1973 U.S. National championship at Suicide Hill in Ishpeming, Michigan, Jerry was in perfect Daescher* flight form.

Daescher* – the predominant flight style from the late 1950’s until late-1980’s, illustrated by skis parallel and close together and the ski jumper’s torso bent slightly forward, with arms close or touching at the hips. It may also be noted that goggles were not popular and helmets were yet to be introduced to the sport.

What knocked it out of the park for me was that prior to these achievements, in September 1971, he permanently lost his right eye to an industrial accident. Amazingly, he overcame that deficit in depth perception, a critical ability in a high speed airborne sport covering long distances and elevation changes over a sometimes difficult to distinguish terrain.

2 - Local Beginnings

2.1 – Section 12 Legacy

Our dad, Wilbert (Willie) Savonen, was born and raised on a modest 40 acre dairy farm along Section 12 Road in Ironwood Township, along with brothers Toivo (Toyk) and Elmer, and sister Helen. John (Juho) Savonen, wife Hilda, and their 6 year old son Onni (Willie’s father) emigrated to the U.S. from Finland in 1909 having already lost an infant and a toddler to disease, reflecting rampant mortality rates of the time. Fortunately, the family elected to escape their homeland before rising political turmoil escalated into a brutal civil war a few years later.

Finnish was the primary language in the Ironwood Township home. It was not unusual in a first generation family that conversational English was not learned until reaching school age. So, in addition to an accent, there was special flavor how words were pronounced. For Dad and his generation, it was natural for the ‘h’ to be silent in the ‘th’ combination, and a ‘j’ sounded like ‘y’, as it is today across broad swaths of Europe. As such, the pronunciation of the common Finnish name Juho was ‘YOO ho’. A sample Dad expression, when he intentionally embellished it, would be “Da troot ist tat skee yumping is a trill.”

Dad also had the tendency to introduce a few malaprops, and some not by design. When encountering stubbornly rusted bolts in a backyard repair job one day with me, his 11 year-old son, at his side, he impatiently directed “Go get the profane torch”. After a moment’s pause, we realized what had been said, and shared a hearty laugh. Actually, the word fit his moment of frustration.

For a small dairy farm to remain operational, repair ingenuity was a necessary skill for the Savonen boys. As a practical, hardscrabble solution, hay bale wire kept many of the farm implements functioning until a more thorough and durable repair was possible, even if the initial repair was neither aesthetic nor found in repair manuals (that often didn’t exist).

Willie and older brother Toyk were always outside. The Savonen dairy farmhouse was perched on a rise overlooking idyllic Siemens Creek that bisected the property. They fished for brook trout and raised extra cash by trapping muskrat along its banks. Strenuous farm chores didn’t quell enthusiasm for sports when time permitted. Whenever possible, they rounded up the neighborhood boys to play ‘unorganized’ baseball. Even though the neighborhood consisted of miles between bustling farms and party line phones, youngsters gathered to play ball without relying on adult presence or organizational oversight. The baseball field for them was the local gravel pit where bad hop ground balls were an accepted part of the game, and not shying away from the erratic bounce was a measure of toughness.

In the U.P. snow belt winter, skiing was the favored pastime. Alpine skiing (or downhill as it is often called) was ‘nice’, but the local alpine ski hill industry was small scale in the 40’s and 50’s. Mount Zion ski hill ski was more than four miles from the Savonen homestead and lift tickets cost money (OK, but a nickel was still real money in ‘toes’ times). And even though both cross country skiing and ski jumping had already appeared in the 1924 France Olympics, local ski touring was a novelty and groomed trails were only a concept.

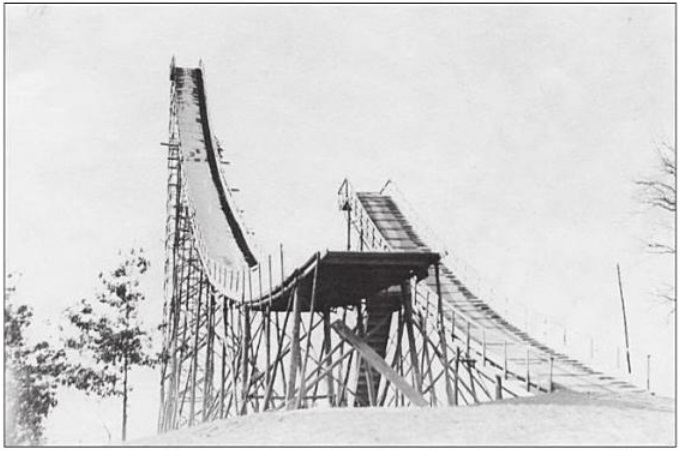

As Supercynski (1) documents so well, ski jumping reigned as the preeminent local sport of the early 20th century. Ski jumps of all sizes and shapes could be found in so many of the hilly neighborhoods across the U.P. The Ironwood Ski Club formed in 1905 and built the 40m* Curry Ski Hill ski jump. In the ski jumping community, Curry Hill was famous, with the ski jumping world record of 152 feet set in 1911 by Anders Haugen and extended to 169 feet in 1913 by Ragnar Omtvedt. Later that year, a severe wind storm knocked down its wooden scaffold. Rebuilt in 1923, its steep and slender steel girder construction relied on a web of guy wires to stay upright. Not to blithely assert that ski jump design standards were lax, but it was not unusual that ski jumping scaffolds met their demise in high winds, as was Curry Hill’s fate a second time during a 1930 storm. Rumors persist to this day that vandals cut the guy wires, thus guaranteeing its doom. Actually, all 11 ski jumping scaffolds constructed in the region by one particular Chicago company collapsed or fell prey to high winds and storms in the 1920’s and 30’s (1).

40m* – in simple terms, (m) denotes the nominal jumping distance (in meters), as designed for the hill.

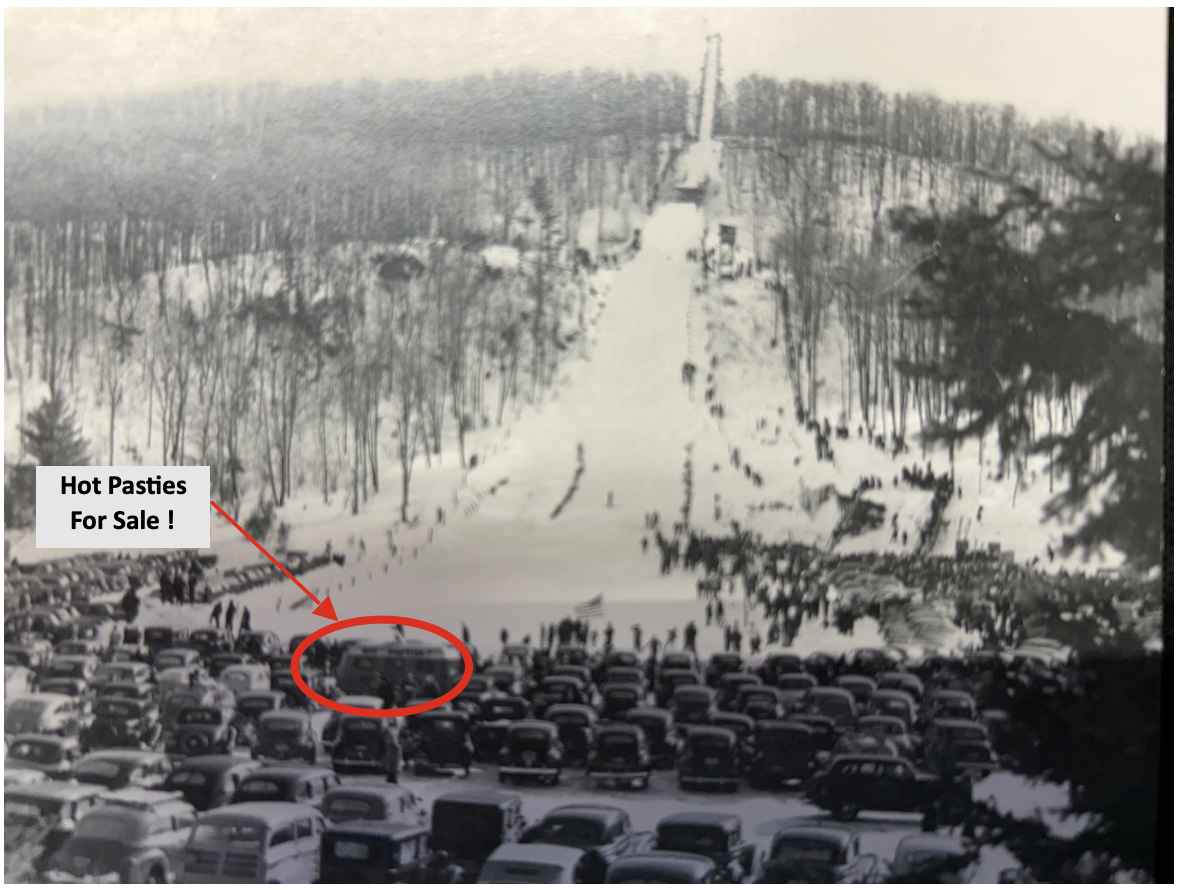

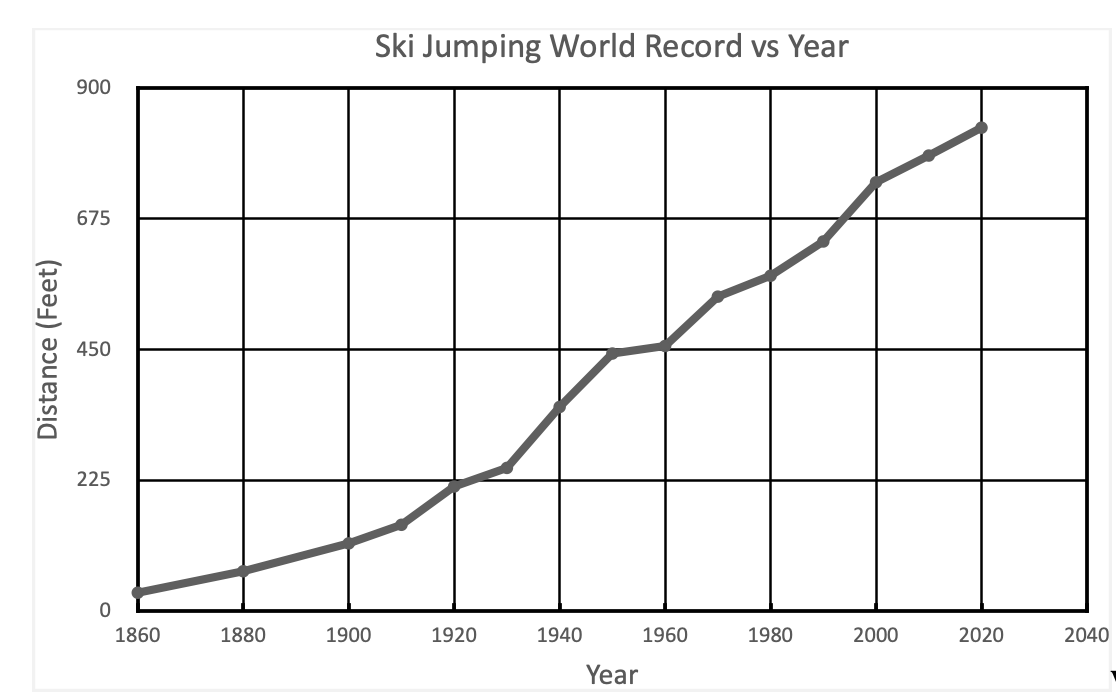

So in 1935, the Ironwood Ski Club built the 50m Wolverine ski jump in Ironwood Township. It hosted one of the more prominent annual tournaments in the national ski jumping scene. Wolverine was built on a ridge enabling jumps in excess of 200 feet. The sideshow of setting a world distance record (which exceeded 300 feet by 1935) had shifted exclusively to the larger international hills. Nevertheless, Wolverine ski jumping tournaments were a spectacle, attracting patrons from across the upper Midwest region who wanted to see intrepid heroes of skill and daring soar (very) high through the air, if not tumble to the bottom.

Among the ski jumping legends that Dad described to me, the exploits of Norwegian immigrant Torger Tokle were prominent. Tokle set the Wolverine hill record of 216 feet in 1942. National newspaper articles were calling him the “Babe Ruth of Skiing” (5). In a 4-year span (1939 – 1943) after migrating to the U.S., Tokle entered 44 tournaments and won 39 of them. Torger’s heroism was immortalized when he joined the U.S. Army and died in a 1945 World War II battle.

As indication of the Norwegian passion for skiing, all twenty of his siblings skied and two of his brothers (Kyrre and Art) eventually migrated to the U.S., becoming established ski jumpers and coaches in their own right. If marketing had been more sophisticated in that era, a prized pair of new jumping skis would have been marketed as Air Tokles, some 65 years prior to Air Jordans.

Since Wolverine was less than a mile as the pheasant flies from the Savonen farm, I imagine preteens Willie and Toyk enthralled while watching local ski jumping heroes like Ted Zoberski performing in their own backyard. In their teens and early twenties, Willie and Toyk regularly rode Wolverine, with Toyk competing in the official tournaments. At 5 foot 7 and 130 or so pounds, the Savonen boys were farm boy tough, wiry, and quick as snot, a physique that ironically served as the prototype for ski jumpers in the 21st century, rather than 1950.

After a day of jumping at Wolverine, they ski toured across the neighbors’ farm fields to get back to the lower lying Savonen homestead. If the snow was old and crusty, they glided effortlessly over the top of it with their heavy, stiff hickory skis.

Even though traveling long distances in the dead of an upper Midwest winter in a 1930’s or 1940’s automobile could be a precarious undertaking, the crowd size at Wolverine and other prominent ski jumping venues like Suicide Hill in Ishpeming routinely numbered in the thousands. Numerous vendors capitalized on the community event by selling culturally specific cuisine (doused with ketchup, of course!).

Alas in 1963, the Wolverine ski hill scaffold was partially destroyed. Yeah, you guessed it. The culprit was a severe wind storm. A partially reconstructed inrun ramp enabled periodic use of a scaled down Wolverine from the mid-60’s until the early 70’s for practice and local or unsanctioned competitions (1).

2.2 – Slab Riders

Fast forward to the mid-1960’s, Willie and wife Shirley (Mom) are raising daughter (Wendy) and son (me). My first ski ride was on Dad’s shoulders while he glided down the gentle seven foot slope from our Ironwood Aurora Location house to the Richards’ yard next door. For that occasion or when going to Mt. Joy in Wakefield, he brushed on layers of pungent smelling shellac and then rubbed on paraffin wax of the appropriate color for that day’s snow conditions onto his three groove hickory jumping skis. Somewhere in the basement, he found and dusted off his low-cut leather jumping boots that hadn’t seen snow in a decade.

In contemporary terms, a slab rider is someone part of the culture that creates customized vehicles known as slabs. In the broader skiing world, a slab rider is a backcountry skier who may find themselves on top of an unstable slab of snow that could trigger an avalanche, leading to their untimely demise. But for local Yoopers, slab rider was a simpler, but less than complimentary name (but not quite a slur) applied by non-skiers to all alpine skiers and their wooden slabs.

The initial love of slab riding for Wendy and myself got legs (and skis, of course) when our parents scrounged up money for the less expensive local alpine ski hills, such as Eagle Bluff (Hurley), Mt. Zion (Ironwood), and occasionally Whitecap (Upson). It was a treat when we were dropped off for three hours of Wednesday or Saturday night skiing at Big Powderhorn Mountain. The occasional splurge was a full Saturday’s worth of skiing.

At Powderhorn, the technique for using the bunny hill rope tow was not intuitive for this 7 year-old. After a few face plants and near tears in public, I eventually mastered it by gradually, rather than suddenly, tightening my grip on the moving rope. After bearing with snide comments by a rich bunny hill brat about my cheap and undersized ski equipment and persuaded by big sister Wendy waving gleefully and proudly from the chair lift overhead, I was motivated to graduate. When venturing to the top of 600 vertical foot Big Powderhorn Mountain, I realized that although the green circle (easiest) and blue square (intermediate) ski runs were much longer, most hill sections were neither steeper nor more difficult than the steepest part of the bunny hill. It was an early lesson to maintain poise and confidence while graduating step by step to ever larger ski jumps.

Even though it was an alpine ski area, we’d tend to ski off trail, dodge trees, and create small kickers (small jumps with an upward ramp) on the side of the main trail to practice rudimentary acrobatics. By the way, when propelled vertically by a kicker and landing a short distance later on flat ground, the impact on the skier is far greater than landing on any well designed ski jumping hill after flying hundreds of feet.

Anyway, these antics paled in comparison to the somersaulting stunts of off-trail hotshots with last names like Noren and Bertini in full view of chair lift riders overhead. At that time, only a few could admire the radical skills of these predecessors of free style skiing which now attracts national and Olympic attention. Fun-killing ski patrollers would eventually come along, and in the name of safety, rope off ungroomed trail sections or have youth-made bumps eradicated by hill grooming machines.

When we weren’t obeying signs posted along the runs, we sought additional excitement. On a clear, dark night, a ride up the chair lift offered the opportunity to check for Northern Lights, try to name constellations, and watch for a shooting star or high-flying jet. To keep our adrenaline pumping, and on a whim under the cloak of darkness, we would contort ourselves to swap positions on the two-seater chair lift while dangling 30 feet above the ground. Why? I don’t know. Because it was daring and a challenge.

Yet, the sibling standard for adventurous thrill seeking was pioneered by my sister (in her younger days). She boldly jumped off the Powderhorn chair lift one evening, as if it was a logical thing to do. As with some daredevil acts, the actual risk is less than the risk perceived by an observer. She jumped from a negotiable height into deep snow after removing her skis. The real risk was that the ski patrol would notice her shenanigans and pull her ticket!

Later, she trumped that adventure by somehow navigating her way to the very top of the monstrous Copper Peak ski flying hill scaffold while it was still in the finishing stages of construction. Chain link enclosures protecting the open-air walkways were not yet in place. I wouldn’t hazard to do that then or now, and I was supposed to be the risk-taking ski jumper of the family.

3 - Junior Hills

3.1 – Iron Bowl Shapes

Throughout the U.P. in the early 1900’s, it was common that employees and their families lived in modest housing on hills in proximity to actual mining operations. The Aurora was one of a string of mines situated across the east-west Gogebic Range that briefly led the nation in iron ore production, peaking around 1930. By 1967, the last high-quality ore railroaded out of the Gogebic Range and the mines closed. Steep, miniature mountain ranges of rust-orange iron ore tailings and abandoned mining structures left behind were an imposing and somber testament to the industriousness of the first half of the 1900’s.

Acknowledging limitations of the scaled down Wolverine after the 1963 storm damage, the ardent Gogebic Range Ski Club (GRSC) committed to re-energizing local and youth ski jumping. The Caves provided a convenient location. As named locally, the Caves are the east-west orientated land subsidence originating over the abandoned underground mines just three city blocks southeast of downtown Ironwood. There are no known open crevices, or caves per se, but Caves is vernacular for cave-in. It is a 1½ mile long by ¼ mile wide ravine with one side faced with 25 - 75 foot cliffs of dark rust iron rock. Decades before creative volunteerism established today’s Miner’s Memorial Heritage Park, the Caves were an unofficial local playground for snowmobiling, motorbiking, juvenile exploration, and multiple ski jumps.

The Caves location directly opposite the Ironwood Little League field became the chosen venue for a new family of ski jumps. A few hundred yards west of the municipal landfill, the so-named Iron Bowl had ski jumps ranging in size from 10m to 30m created on the Caves steep slopes.

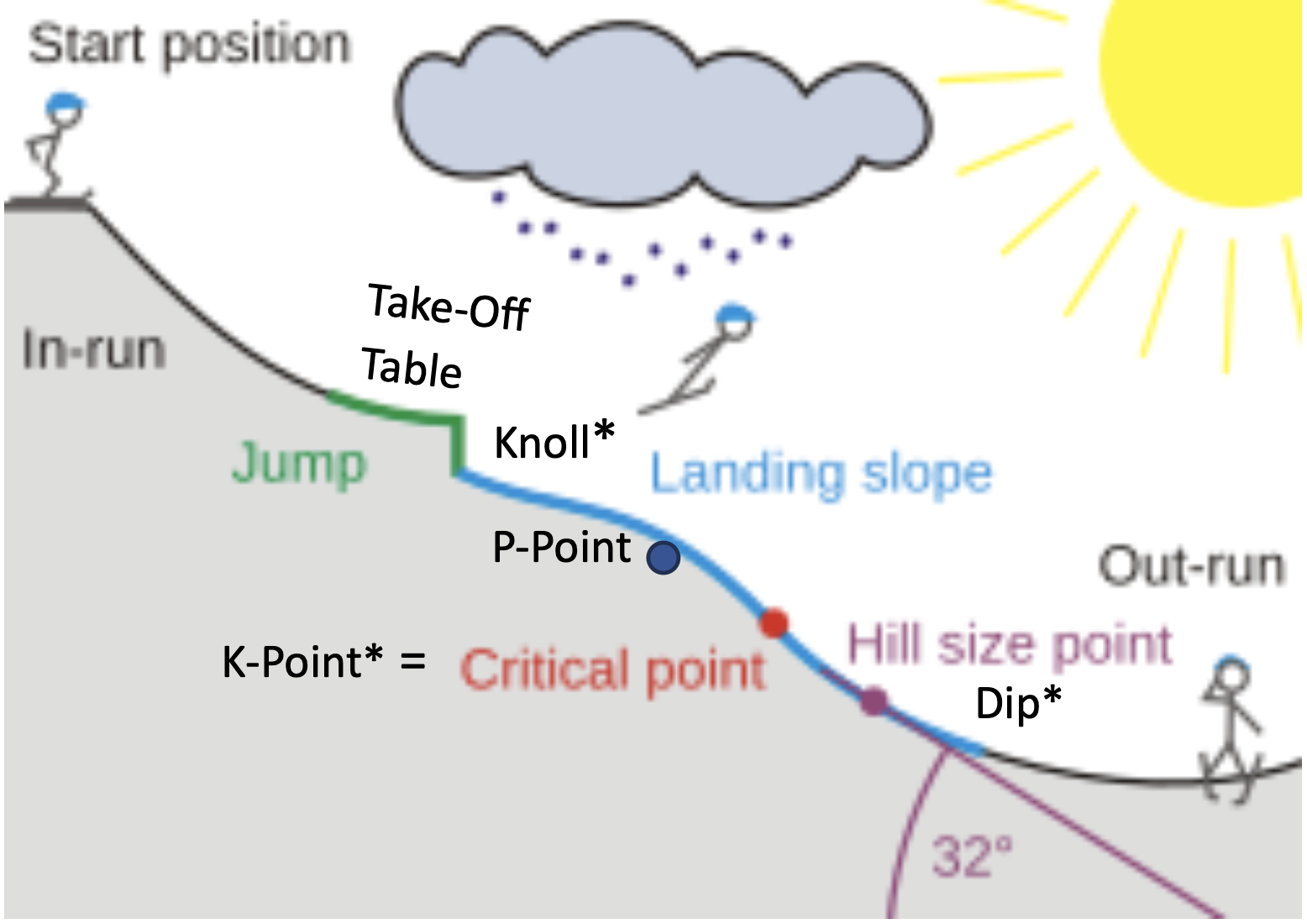

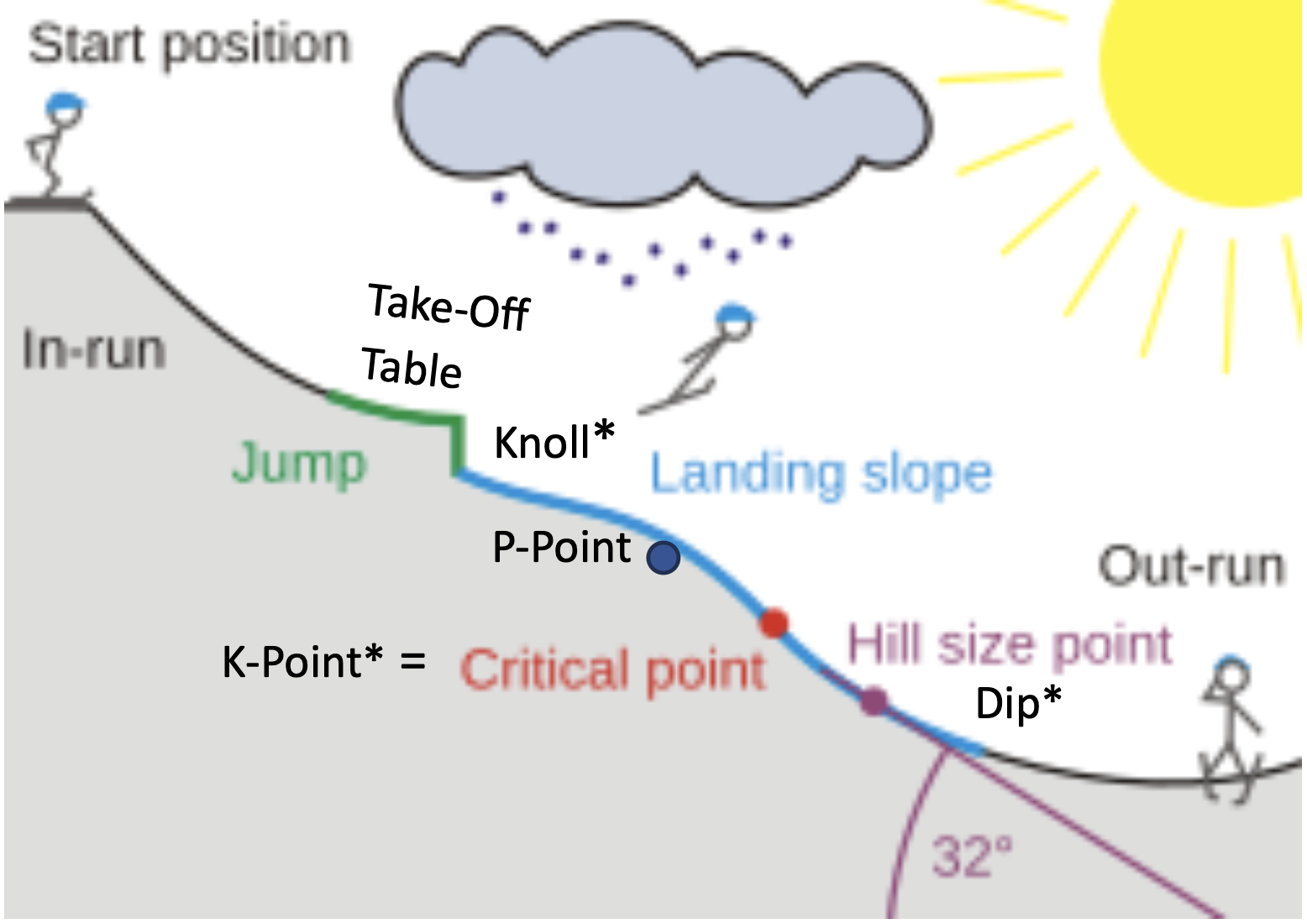

The ski club exploited the unnatural landscape by designing and grading a set of two ski jump landing hills out of the iron ore mining recesses. The primary ski jump was the 30m, where jumping distances in excess of 100 feet were readily achievable. The contours of the inrun and landing were designed by Supercynski in compliance with evolving jumping hill design standards. The jump hill architecture called for 10° downward slope at the end of jump take-off, a relatively long knoll, and a contoured landing hill. It ensured flight trajectories rarely exceeded 10 feet off the ground. This was in stark contrast to flat take-offs and extremely high flights prevalent during the early history of the sport.

The 30m inrun was part artificial (scaffold) and part natural (graded iron ore tailing slope) so it was in the minority of Midwest jumping hills. Most of the smaller jumps in the Midwest had inruns that were either all scaffold, or all natural. The upper half of the Iron Bowl inrun consisted of a 25 foot high scaffold of creosoted telephone poles and frugally obtained plank lumber. The scaffold merged into a graded rock slope transitioning to the take-off table. Construction of the Iron Bowl was completed in time for the inaugural meet in 1969.

Not unusual for smaller jumping hills, it had only one starting level at the top of the inrun. To start the Iron Bowl ride, the jumper pushed off with the tail of one ski from the backboard on the top platform of the scaffold. To gain more starting speed, a game within a game would be to fire out from the top of the scaffold, practically leaping onto the beginning of the inrun track. Another technique was to tip into the track, then take a few rapid cross country skier strides, before dropping into the aerodynamic inrun crouch. The resulting inrun speed benefit was debatable, but at least the jumper looked like he was all-in.

In the 70’s, larger jumping hills usually had multiple starting gate platforms angled into the main inrun track at different heights. The gate chosen for that day (or that competition round) was based on the speed of the inrun conditions and how far jumpers were flying in practice or the previous competition round.

At the Iron Bowl, the adjustment of inrun speed was more rudimentary by simply cutting back or adding to the length of the take-off. Since the Iron Bowl had an oversized landing hill in proportion to the inrun, this approach worked fine. Although the longest jumps at the Iron Bowl rarely exceeded 120 feet, the landing hill slope was capable of handling even longer distances.

On today’s major hills, the opportunity to gain a starting speed advantage is all but eliminated. The jumper cannot aggressively push off at the start, but begins the ride by gently releasing from a sitting position on a horizontal bench notched in the center of the track. The bench is positioned incrementally higher or lower on the inrun ramp in response to track speeds of the day.

Inrun speed is maximized by maintaining a quiet, aerodynamic crouch. A heavier jumper and heavier skis naturally generate higher inrun speed. But, once in the air, greater weight and gravity conspire to oppose longer flights, especially on bigger hills with modern hill profiles. Moreover, for an increasing number of contemporary larger and international hills, the inrun track surface is comprised of artificial surfaces. They treat ski friction with less skier-to-skier bias than snow over a range of temperature and humidity conditions.

Since the Iron Bowl hill was in a ravine of sorts, the second half of the outrun rose steeply on the opposite side. Unlike most other ski jumping hills, the skier did not have to brake to a stop. With the rise of the outrun naturally slowing the jumper, a jumper could jump turn 180° and enjoy a gentle downhill ride back to the bottom of the landing hill. It saved walking distance and time before removing skis and climbing up the landing hill for the next ride. As secondary entertainment on icy nights after a January thaw, we would ride far up the outrun hill, and return with speed up a greater part of the landing hill.

Ironwood had a dubious advantage over most other regional ski jumping locations, as it received more snow over a longer calendar period (from before Thanksgiving until at least mid-March). Since most of the tournament circuit didn’t begin until early January, our club could use late November and most of December as our own preseason practice. Conversely, if heavy lake effect snowfall continues throughout the winter, it adds to the arduous chore of hill preparation.

Snowmobilers were the bane of the ski jumping community. Not as damaging as some mischievous, alcohol infused rogue running a pick-up roughshod over a golfing green, it was not uncommon to find snowmobile tracks on the landing hill when arriving for another day or evening of jumping. It was not surprising that a steep, firmly packed and nicely groomed hill tempted wannabe Evel Knievels with sleds. But it was a form of vandalism, creating disruptive ruts on the landing hill that had to be repaired. Ironically, a few decades later, the huge Copper Peak landing hill became the site for officially sanctioned snowmobile hill climbing competitions when ski flying was not scheduled.

3.2 – Launch and Learn

Dad was curious whether his son would like ski jumping. So, on the rock outcropping 100 yards up the road from the Savonen Aurora Location home (where aurora borealis was viewable on a clear night), he shoveled a ski jump into existence. Two goldenrod weeds marked the jump take-off. For an 8 year old, it was Olympic size. With a neighborhood schoolmate and myself the only riders in its brief history, the final hill record plateaued at 28 feet, or a bit short of the 1808 world record of 31 feet. With abandoned mining structures at the top of the hill precluding creation of a longer inrun and greater takeoff speeds, the hill record was secure. Nevertheless, the ‘trill’ of jumping was instilled.

With a new set of Iron Bowl jumping hills in place, GRSC launched a concerted effort to build the foundation of a ski jumping program, aided by local advertising. Though the quiet Finlander that he was, Dad had ears to the ski jumping community. By then in his late 30’s, Dad had fond memories of the defunct 30m Quarry Hill ski jump previously located in the Caves east of the Iron Bowl, where he competed in the early 1950’s. However, his favorite ski jump remained the 35m Dynamite located just north of US2 and west of Section 12 Road on a bluff less than two miles from the original Savonen farm.

So, one early winter Sunday in 1970, Dad took me to the Iron Bowl. There were about a dozen jumpers present, most of them using the largest (30m) hill. And that’s where I met Walter (Wally) Kusz, the chief orchestrator. We were enthusiastically welcomed, and after some discussion, I was coaxed to try riding the smaller landing hill.

Snapping on my alpine skis at the knoll*, I mustered the courage and cautiously snowplow turned to head downhill. The hill surface was very smooth. As I steadily picked up speed, I didn’t expect the slope to increase so rapidly and continuously. When I reached the steepest part, and could finally see the bottom of the hill, it felt like I was going straight down. I hadn’t signed up for this.

After another moment of descent, I bailed (sat down), and spun out. Sheepish though I was, Dad and others encouraged me to try again, but lean forward into the downhill slope. On the second try, I did just that and then crouched low to the ground to stay upright through the dip*. By 3rd or 4th try, I conquered the entire landing hill in a wobbly, but fully upright fashion. I thought “I guess I’ll come back next week”.

Knoll* – the relatively flat part of the landing hill starting at the end of the jump (take-off table) and ending after transitioning to a steeper constant part of the landing slope between the P-Point and the K-Point. Jumping hills are designed for ski jumpers to land beyond the knoll on the steeper slope that follows.

P-Point, K-Point, Hill Size Point* – see Appendix I - Ski Jump Classification for a more detailed explanation.

Dip* – bottom of the landing hill, where the hill transition to the flat outrun is nearly complete, and well beyond where ski jumpers can safely land.

Panking* – Yooper term for packing snow on the landing hill by sidestepping with skis.

How time flies! Just 6 years later, I enjoyed my small part in helping prepare the Copper Peak landing hill, holding onto ropes while sidestepping and panking* the hundreds of yards of the 40° sloped landing hill. Besides watching the tournament, my personal thrill as an early teen was the opportunity to ride the entire Copper Peak landing hill while crouched in a ski jumping inrun tuck. It was speed to burn, baby, and no radar in the area. I am sure that it was the fastest that I ever traveled on skis, well in excess of 70 mph considering that ski flyers reach the low to mid-60’s shooting down an inrun that is considerably shorter than the landing hill.

Alongside the inrun of the 30m Iron Bowl jump and its scaffold, a 2-foot high snow bump was angled into the main landing hill, creating a 15m capable jump. Although the maximum achievable jumping distance was 45 feet, beginners could experience the exhilaration of ski jumping and aerodynamic lift for the first time.

We modified my alpine equipment to partly resemble jumping skis, at least so the ski boot heel could lift from the ski, enabling a forward lean in the air like a genuine ski jumper. With alpine ski bindings of that era, the back of the ski boot rigidly attached to the ski by a cable wrapping around the heel. By removing the two cable guides on the sides of the ski closest to the heel, the heel was free to lift from the ski.

After I used the modified alpine skis for a few months, Dad obtained a set of used, but actual jumping skis. Real jumping skis with wood-fiberglass composite core and five grooves on the plastic bottoms! They were 50% wider, 70% longer, and four times heavier than my little alpine skis. If I happened to be alpine skiing the evening immediately following a day of ski jumping, muscle memory made those alpine skis feel like toothpicks.

Those dark blue Elan jumping skis provided an early 70’s luxury Cadillac smooth, muscle car Trans Am fast ride. In a drag race down the landing hill, anyone with jumping skis would surge past the alpine skier like cars passing Dad’s ’59 Studebaker struggling up Birch Hill. At 255 cm long (8 foot 4 inches), the jumping skis were eight inches oversized for my five foot and change height at the time, but I didn’t care.

During ensuing weekends, a few of us youngsters were introduced to the actual sport of ski jumping. While Dad facilitated my interest and introduction to ski jumping, Wally Kusz was my first (and essentially only) ski jumping coach, with all due respect to many others who gave me an occasional tip or guidance over the years. With a distinct accent, as did nearly every first or second generation Yooper, he exuded an infectious enthusiasm. He had a keen eye for identifying minor deviations from the fundamentals that he knew yielded success on any jumping hill. He would persistently emphasize;

- “In the inrun, keep your shin angle forward, back flat and level, and head up.”

- “It’s all in takeoff.”

- “Timing is crucial. Don’t jump too early or too late.”

- “When you jump, explode, keeping your chest down, and head level.”

- “Never drop your head.”

- “When in the air, your body follows your head, just like a bird.”

- “Look out over your skis and stretch for the bottom of the hill.”

- “Remember - Never, ever drop your head.”

Wally described the lift during the early stages of flight over the knoll as someone grabbing you by the back of your belt. Until then, my only experience of someone grabbed and lifted by the back of the belt came from observing our fourth grade teacher and a misbehaving classmate. One day he escorted the petrified classmate horizontally out of the classroom by the back of his belt, while he frantically hand surfed across classmates’ desks on the way to the principal’s office. Well, that was 1969 classroom discipline.

In a not so obvious parallel to hitting a baseball on the sweet spot of the bat barrel, a perfectly executed ski jump produces longer distances with seemingly minimal effort. Keys to achieving that ski jumping sweet spot is nailing the timing exactly with a quick and powerful take-off and transitioning quickly and smoothly to an optimal flight position. The fruits of all that are extra lift, and after clearing the knoll, an extended, almost weightless flight peering over skis and sighting beyond the hill bottom.

While the primary event during the Iron Bowl junior ski jumping tournaments was the 30m hill, we had the opportunity to be ski jumping competitors for the first time on the 15m junior hill. Prior to the 30m big boy meet, I soared 37 feet and 1st place. I was hooked.

Meanwhile, that big 30m jump began to quietly taunt us. “Can you handle me?” or in Yooper barnyard language “Or, are you chickens@&t?” So, one Saturday afternoon while the senior ski jumpers were competing at a late season out-of-town tournament, my neighborhood buddy Todd and I put on our skis and skated the half mile of Caves snowmobile trails from home to the Iron Bowl. We were determined to scale the monster for the first time.

The cardinal rules to ensure safe ski jumping (besides proper technique) include;

- Never jump alone.

- Prepare the hill adequately.

- Ensure mature supervision.

- Use the hill and equipment as designed.

Well, between the two of us that day, we weren’t alone (check) and the hill was in good condition (check). But, we fell short of the last two rules. We convinced ourselves that it would be safer if we limited takeoff speed by starting only halfway up the 30m inrun. Neither of us were educated in basic physics that dictate fighter jets use the full length of the aircraft carrier runway to avoid plunking into the sea.

With our take-off speed compromised, both of us soared into the air and then stalled midair like Wile E. Coyote overshooting a cliff. We should have been holding his “Uh-Oh” sign before plummeting to the ground. The flights were short and impactful onto the nearly flat knoll. It hurt more than a little bit. Both of us wiped out, but being young and flexible, we were uninjured. We had had enough for the day. Being that it was March, our jumping season was finished for the year.

3.3 – Yooper Juniors

The Iron Bowl was our home hill from 1969 thru 1975. During the 1971 jumping season, some of us graduated to the 30m hill. As previously experienced, appropriate use of the 30m jump required using the entire length of the inrun scaffold. It was a mental commitment walking up to the top of the 25 ft high scaffold for the first time. No one would dare ostracize a first time rider who decided to walk back down. For me, it was cool to be at the top of the scaffold with the senior jumpers. Any lingering concerns had been swept aside.

Before launching down the inrun for a practice ride on most small hills, the next jumper yells down to a spotter (usually a fellow jumper or coach) on the knoll who has a clear view of the entire hill to confirm that there are no obstructions or people in the path of the skier. Having received a clear affirmative response from the knoll, it’s go time.

Pushing off from the top of the scaffold for my first 30m ride, I settled into the inrun track. Accelerating with each passing evergreen twig marking the inrun track, it took so long to get to the takeoff. And then, the last bough at the end of the inrun finally arrived, and it was time to leap. Even though it was a short flight for the scale of a 30m jump, the flight was much higher and longer than what I had grown accustomed to on the 15m, or the ill-conceived half scaffold ride. Yet, the landing was much gentler. A long ride down the rest of the landing completed my personal victory. After a few days of gaining confidence and beginning to do more than just ‘surviving’ the hill, it was time to start earnestly addressing details to become a competent ski jumper.

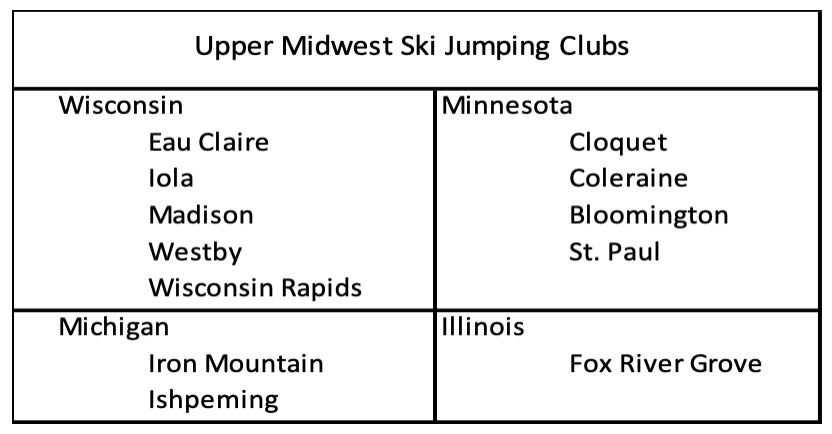

Ski jumping is governed nationally by the United States Ski Association (USSA), organized across the country by divisions (or regions). In the 70’s, there were well over two dozen active ski jumping clubs in the USSA Central Division at that time, encompassing the western U.P, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and northern Illinois. By registering with the USSA, a jumper would receive an ID card and gain access to enter tournaments.

Junior USSA members were subdivided into four classes by age:

- Class 1: 16-18 years old

- Class 2: 14-15 years old

- Class 3: 12-13 years old

- Class 4: 9-11 years old

For Ironwood junior jumpers, the close-to-home 30m tournament circuit was usually scheduled as one day events from late January until mid-February passing through Ishpeming, Iron Mountain, and finally Ironwood. Akin to a small athletic conference, jumpers were familiar with their chief competition.

After two months of practice in 1972, five Ironwood junior jumpers headed to the first junior meet of the year at Ishpeming. It was my first out of town meet on a 30m hill and an entirely new experience. I was the only Ironwood jumper in the youngest class. It happened to be -20° F that day, but at least there was no wind. COVID didn’t arrive until nearly 50 years in the future, so I was wondering why half of the jumpers were wearing face masks. “Oh, due to the cold? Really? OK.”

Anyway, I captured 1st place in my class. I was somewhere between pleasantly surprised and stunned. In those days before cell phones or internet, my parents had no inkling of the results until I got home later that evening. Riding back from Ishpeming in the dark corner of the back seat while the teenagers talked about girls and everything else under the sun, American Pie played on the car radio, and I quietly clutched that 1st place trophy like an Olympic medal.

Every ski jump has its own unique character, as was the case the following week in Iron Mountain at the Big Miron junior hill. Whereas the Ishpeming 30m of the prior week had an all-natural inrun, Big Miron’s inrun was all scaffold and seemingly steep. Being a small, but sporty 30m, extra attention had to be given to the aggressive transitions in the inrun and the landing dip. One had to be ready to time the jump while handling centrifugal forces in the inrun appreciable for a hill that size. Seasoned jumpers could utilize the inrun curvature as minor precompression just before jumping. The transition at the dip was also quick, so holding a stylish Telemark* through the entire landing hill required more skill than usual.

Telemark* - In cross country skiing or ski jumping, a Telemark refers to putting one ski in front of the other, with proportionately more body weight placed on the forward ski, and the boot heel lifted off the trailing ski. In ski jumping, style points are awarded (or preserved) for transitioning to a Telemark ski position simultaneously while landing and holding it throughout the rest of the ride, thus exhibiting exceptional balance. A ‘Hollywood Telemark’ was slang for the less skillful, but showy attempt of transitioning to a Telemark position, but only after landing.

Even though the small hill scaffold was not that tall, the climb could still be unsettling for a young jumper accustomed to natural inruns, especially with others whizzing by just 4 - 5 feet to one’s side. On the way up, you had to make sure that your stiff boots didn’t slip on the 37° sloped wooden ‘cattle ramp’ which was never completely clear of ice and snow. Although I never witnessed it, it was conceivable that a skier climbing up the scaffold could have a momentary brain fade and while looking back down the hill, swing his skis into the path of a rider speeding down the inrun. At the top, the tight confines limited three, or at most four, jumpers being able to put their skis down at the same time, quickly strap them on, check equipment, and compose themselves before flagged to go.

Big Miron was Therese Altobelli’s home hill. A phenom in her pre-teen and early teen years, Therese received notoriety as the pioneering female jumper of the era, particularly in the Midwest region. She was steady and stylish, competing equally with the rest of us young juniors. Whether politically incorrect or not in today’s culture, she was one of the boys. The fanfare surrounding her wasn’t her doing, but she was friendly, poised, and took it all in stride, while adults made a bigger deal about it. Therese just wanted to ski jump. Perhaps her most notable ski jumping accomplishment was a few years later in 1978 when she became the first female to ride the famous 90m Pine Mountain, her home hill. In 2017, Therese was elected to the National Ski Hall of Fame, a forebearer of the female U.S. national team that became internationally competitive during ensuing decades.

3.4 – Iron Bowl Culture

The 1972 – 1974 winters were a growth period for the club. Over the summer of 1971, the industrious GRSC leaders executed on foresight to erect lights on the 30m Iron Bowl jumping hill. Evening ski jumping was ‘on’. The lights were indispensable, an advantage several other Midwest ski clubs already enjoyed.

Before then, the opportunities for Iron Bowl ski jumping were limited to weekends. With the ‘state of the art’ mercury vapor lights, from mid-to-late November until early March, jumping was possible nearly every weeknight. It contributed to the number of club jumpers doubling to more than two dozen, with two thirds of us being junior class age (18 or younger). One could complete 5 - 8 practice rides over a 2 - 3 hour period.

Most Iron Bowl jumpers in the early 70’s were accomplished athletes in other sports. While I was in elementary school, most of my fellow local jumpers were high schoolers. It included football, track, and wrestling stars. In a sense, they were the unintentional advocates of today’s sport culture awakening to the physical and psychological benefits of youngsters participating in multiple sports across all four seasons.

During the span of 1972-1974, I was fortunate to be the Ironwood Schools city alpine ski champion in 6th, 7th, and 8th grade. It included the disciplines of slalom, giant slalom, and downhill. In the woulda category, I woulda been the 5th grade champion, too, but I chose the wrong side of the last slalom gate. While in the starting gate, we were warned about the tricky location of the last gate, even though the turn itself would have been easy to execute. It was too much for a fifth grader in his first ski race to process, when notified seconds before launching down the run.

Theron Peterson, the veteran Ironwood High coach of alpine skiing and several other sports, urged me to join the alpine team. I was honored, but regrettably I felt I had to decline. During the compressed winter season, I didn’t know how I could do justice to both ski sports and how my parents could absorb the additional cost of a second sport. Nevertheless, periodic recreational alpine skiing provided valuable cross training that benefited my ski jumping balance and agility, and as mentioned later, the sometimes critical ability to stop.

Left: Dad as a young teenager with his solid hickory skis and three grooves roughly carved into the bottoms, with leather overstraps, metal front throws and cables. Attired with collared undershirt, Christmas sweater, baggy wool pants, brimmed cap, and all purpose leather boots. Savonen dairy farm and gravel pit are in background.

Right: The author as a 12 year old with my Northland wood composite five-groove plastic bottom jumping skis with all metal cable throws, cables, and toeplates. Attired with winter sweater, streamlined stretch pants, leather-nylon jumping boots, soft knit cap, and choppers*. Goggles and helmets were a thing of the future.

Choppers* – Yooper-ese for leather mittens with inner wool liners.

When convening many winter evenings at the Iron Bowl, one acquaints with the jumping styles and personalities of fellow jumpers. The unique challenges and thrills of ski jumping attracted a diverse group. There was little formal coaching, but fellow jumpers encouraged and teased each other good-naturedly.

One of our all-sport high school stars was having a mediocre ski jumping evening. His results didn’t measure up to his own Type-A expectations, despite being unable to consistently give attention to the sport. At the bottom of the hill after what turned out to be his last jump of the night, he ripped off his skis and threw them like javelins twenty yards into the deep snow. Expletives cascaded across the walls of the Iron Bowl ravine. We didn’t see him much after that.

Bob Shea was one of the senior cats still jumping well past age 40, and he didn’t start ski jumping until his 30’s. Although Bob wasn’t a ski jumping Olympian, he had the heart of a ski jumper, integral to the ski club soul for many years. By the late 1970’s, when there were only a handful of us still jumping locally at Wolverine. Bob periodically took a break from cross country skiing to watch a few of our jumps. After complimenting one of my practice rides, he didn’t hesitate to plant the vision of going to the Olympics. Little did he know that that goal was already entrenched in my mind. But, it gave credence to my dream when someone else spoke out it loud.

Another fellow Iron Bowl jumper was athletic, but he wasn’t an athlete, meaning he couldn’t muster complete commitment to the sport. That didn’t lessen the enjoyment he got from recreational participation. Common for most ski jumpers of that time, he was part of a ski jumping family legacy.

On the side, he was reputedly active in small scale pot distribution. Whereas today, each new cannabis business opening of the now multi-billion-dollar Michigan industry is celebrated with mayoral ribbon cutting and a front page story in the local newspaper, in the 70’s it was necessarily underground and stigmatized. Anyway, this free spirit had a fun loving, outgoing personality.

When putting on his skis at the top of the Iron Bowl scaffold one evening, he stepped into the ski toeplates as usual, but absentmindedly forgot to attach the cables to the back of his boots before launching down the inrun. OK, admittedly the Iron Bowl lights did not fully illuminate the top platform of the scaffold and he wasn’t the most detailed oriented guy, or maybe it was just an extra hazy day.

In retrospect, we watched an amazingly smooth inrun ride until he reached the end of jump. At that point, Kaos triumphed over Control. Normally, our buddy had the habit of letting his skis spread apart just before take-off, abandoning the set inrun tracks. Perhaps it was his ‘drawing outside the lines’ metaphor for life. That tendency was fortunate in this circumstance. As he cleared the jump, a detached left ski dived to the left and a similarly free right ski dived to the right. In ski jumping parlance, he was ‘rolling down the windows’, frantically windmilling his arms while flying past us standing on the knoll.

The center of the landing hill waited to receive him as he completed his 35 mph airwalk. Fortunately, due to good jumping hill design, our pal encountered a soft landing and slid down the rest of the landing. He achieved an unofficial distance of 40 feet, although I think his skis flew further. He was uninjured, unfazed, and after trudging through the deep snow on both sides of the landing to retrieve his runaway skis, he was ready for another ride. We all hooted and laughed, and so did he.

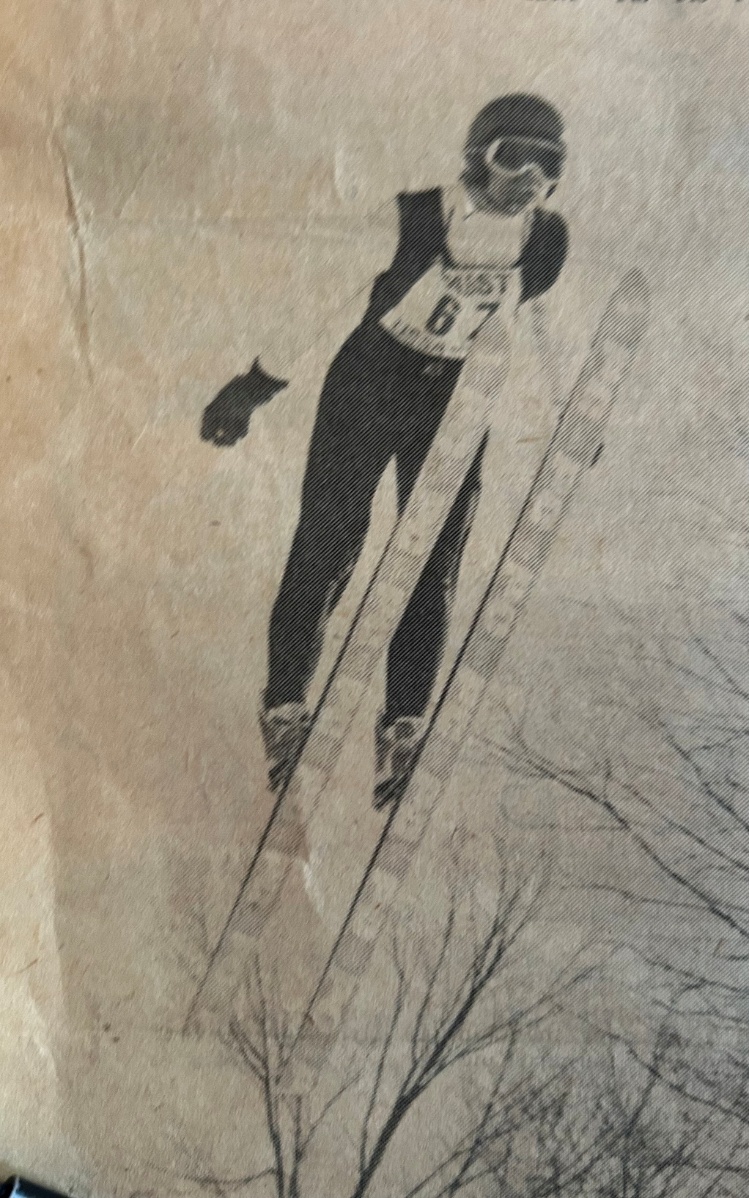

As detailed later, although serious injuries are rare in this sport, the worst case situation is either a head or spinal injury if impacting violently with skis or ground, or cartwheeling down the landing. Helmets didn’t become standard ski jumping equipment until stipulated by the USSA in the mid-70’s. At that time, even ski flyers usually only wore a soft cotton ski cap or beanie. Some ski flyers wore neither goggles nor head covering. Peter Wilson of the Canadian National Team garnered 4th place in 1973 on the massive ski flying Copper Peak hill. As captured below, he approaches the landing without compromising fashion.

By the late 70’s, anyone expecting to compete in a USSA sanctioned meet had to wear a helmet. The first editions of ski jumping helmets were ugly. The available soft plastic cap resembled an early 1900’s bathing cap adorned with colorful soft foam rectangular ridges. For that brief period, it could be embarrassing to a self conscious teen. But, we were all in the same boat probably thinking, but not saying “Hey, you’re a circus clown, too.”

Thankfully, just a couple of years later, the equipment standard had progressed to a classic hard outer shell ‘sphere’, akin to what contact and automotive sports had been using for years. With that type of helmet and goggles in place, I felt safe in my own little cocoon, regardless of the size of the hill or others around me.

4 - Midwest Hill Circuit

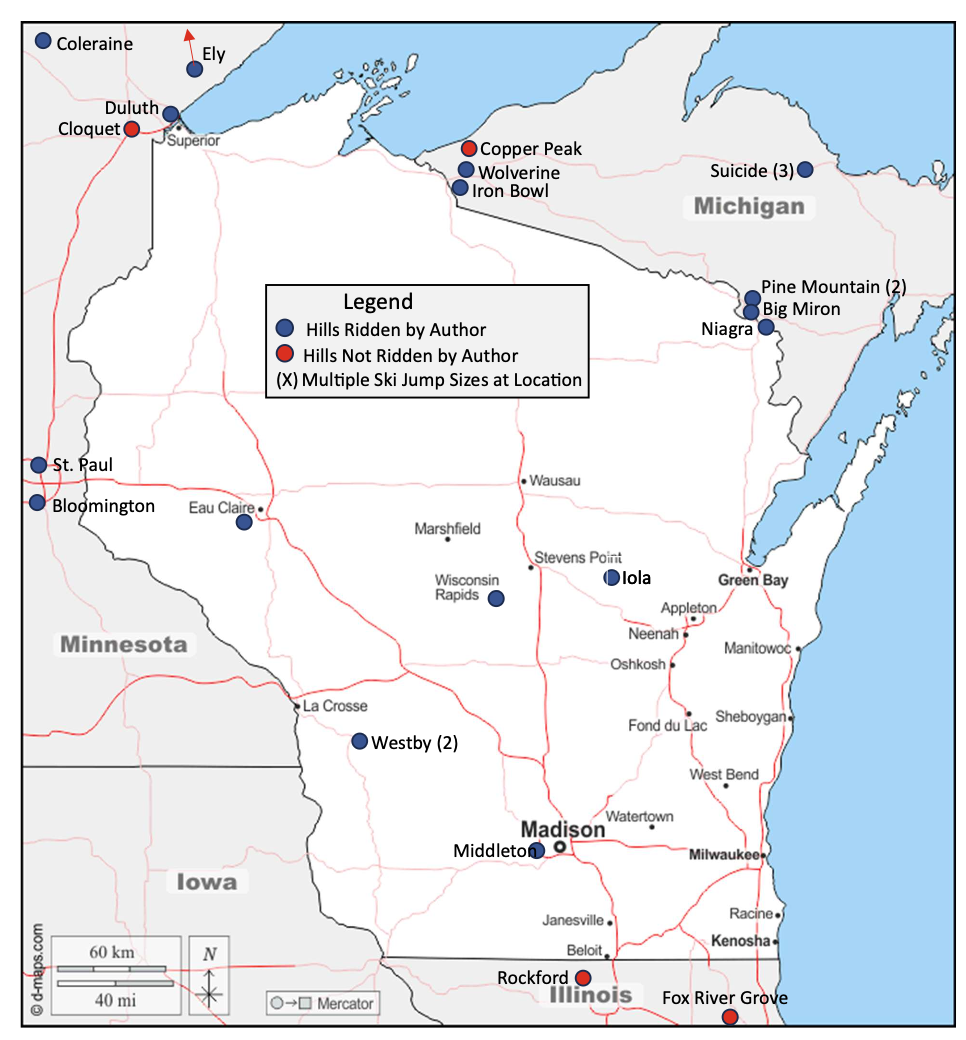

During the 70’s and 80’s, the upper Midwest ski jumping tournament circuit covered the western U.P., southern half of Wisconsin, eastern Minnesota, and northern Illinois, as mapped below. On each winter weekend, there were usually two or more senior level tournaments simultaneously occurring somewhere. A USSA coordinated schedule enabled ski clubs to reserve their calendar for multiple years. I had the privilege of riding most, but not all, of the intermediate and large ski jumps in the region. Due to meet cancellations or personal scheduling conflicts, I never had the chance to ride the ‘far south’ hills in northern Illinois, i.e. Rockford and Fox River Grove.

4.1 – Wolverine Regenerated

After Wolverine was damaged in 1963, it left a gap in the intermediate hill size for local jumpers to train and prepare for senior level competitions elsewhere. The partially repaired Wolverine in use from the mid 60’s until early 70’s was handicapped in that it was neither shaped to contemporary specifications nor consistent with its original design roots. It was a hybrid of sorts. The partially salvaged inrun had a steep top half, followed by a sharp transition to an exceptionally long takeoff table. So, although it couldn’t be used for sanctioned competition, it was periodically used to experience Wolverine’s big air ride.

Before Wolverine was re-established in 1975, I was impressed how a few of the more experienced Ironwood jumpers, such as John and Mike Kusz, Bruce and Gene Harma, Russ Anderson and a few others could venture to ride the large 90m hills like Pine Mountain or Westby, even though their preparation was primarily limited to the small 30m Iron Bowl, the scaled down Wolverine, or brief tournament opportunities on a few other intermediate size hills.

The smaller 30m Iron Bowl was not a long term solution. A limited number of years remained for continued use of the Iron Bowl, since the Ironwood municipal authority was looking for more landfill space in the Caves property that they controlled. And more problematically, with years passing since the underground mines were abandoned, the steadily rising water table would eventually peek above ground in the bottom of the Caves ravine.

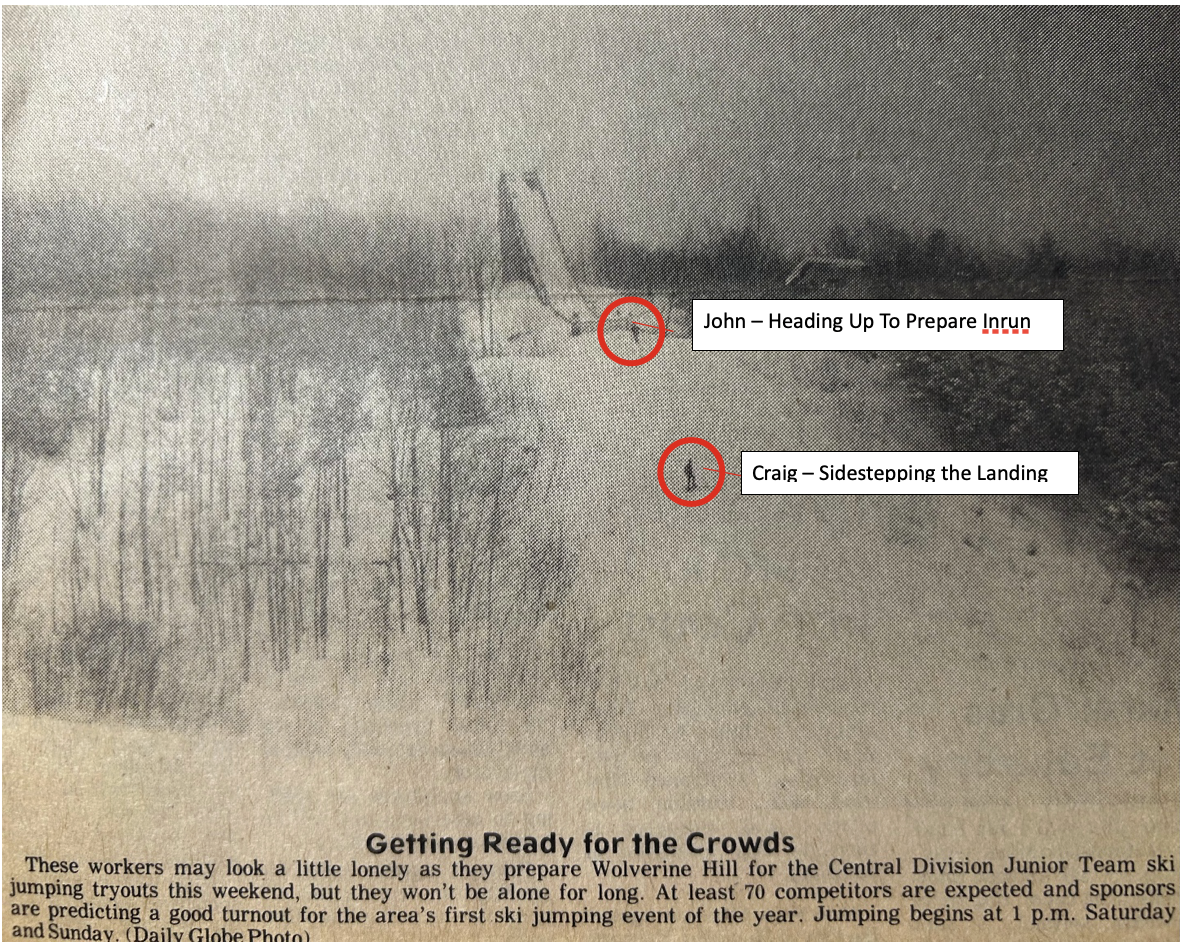

It took forethought, expertise, and determination by several stalwart members of the ‘Greatest Generation’ to rebuild Wolverine and put it back on stage in 1975. To bring Wolverine back to full function, the ski jumping community was fortunate to have the unflinching commitment of a relatively small group, led by former jumpers, such as Wally Kusz, Bob Shea, Frank Pribyl, John Kusz, Gary Kusz, Charlie Supercynski and others that I apologize for failing to recall or being unaware. Others with modest personal ski jumping history were also very active, committed supporters, such as Ernie Mattson, Ed Lakner, and Don Bull. Their altruistic, behind the scenes support was extensive, inspiring, and necessary.

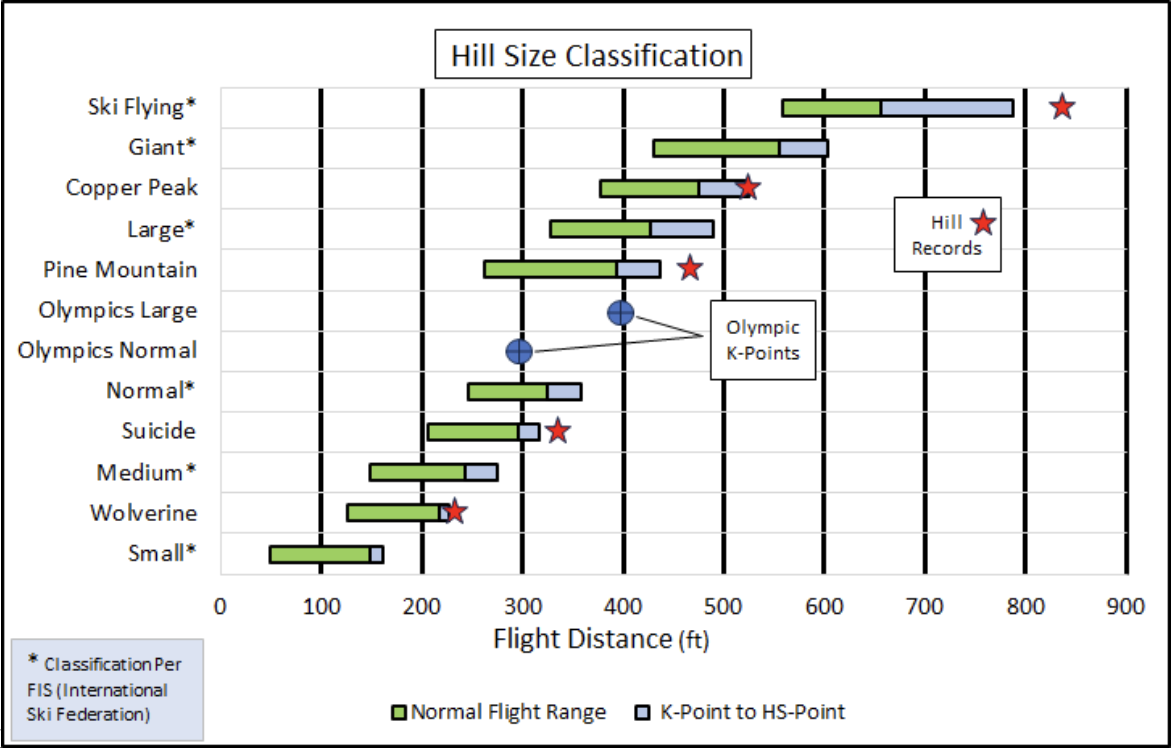

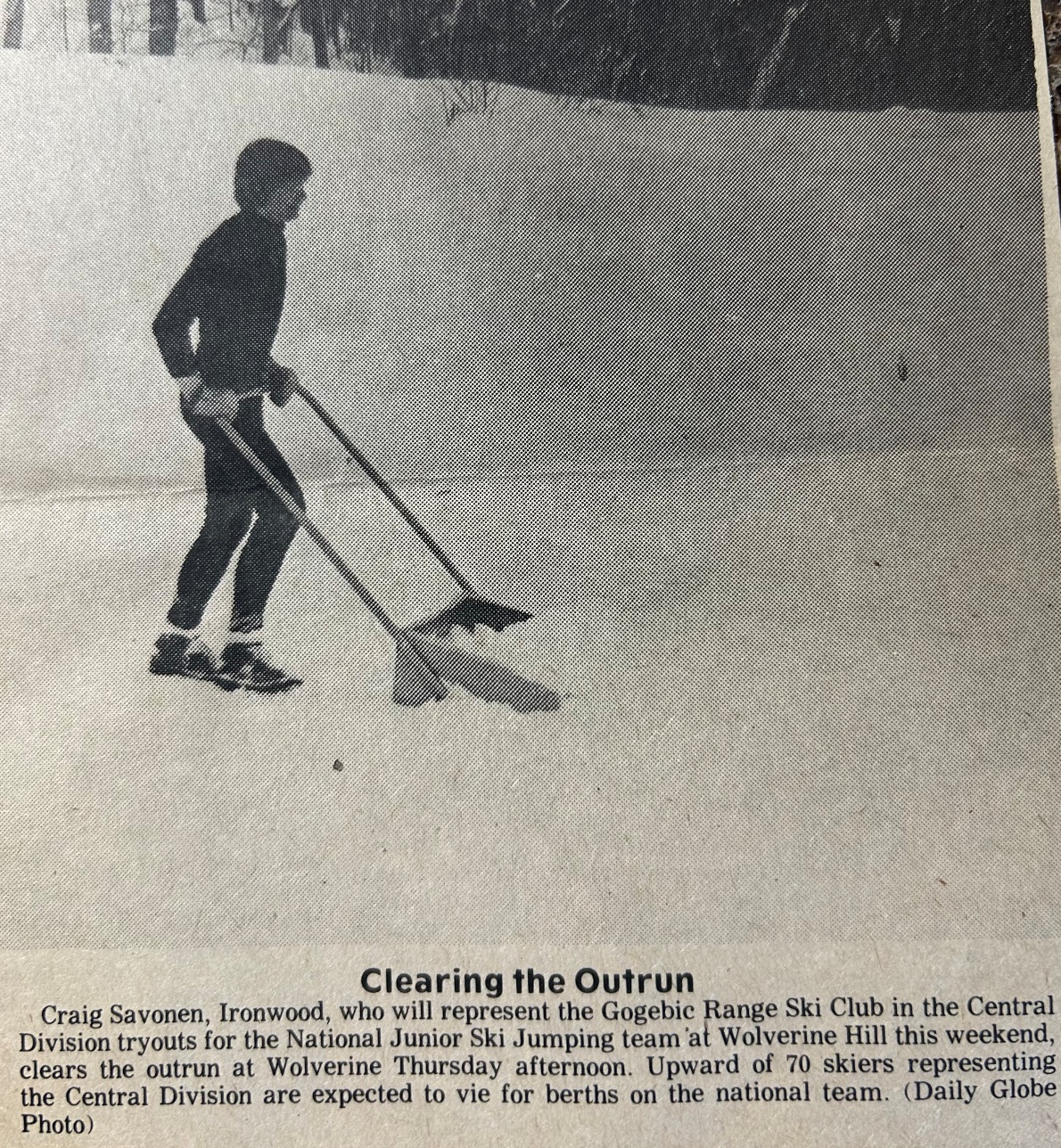

The entire Wolverine jumping hill had to be re-contoured to the updated profile. Supercynski led the redesign and summarized the cost efficient material and labor (1). It took intensive effort by a modest size crew to get Wolverine back on its feet, including re-profiling the landing hill, reshaping a longer knoll, reworking the entire inrun slope by moving tons of earth, and constructing an entirely new scaffold on top of it. With the complete revision of Wolverine to prevailing 1975 hill standards, the region could once again point with pride to the historic 55m (sometimes called 50m) ski jumping hill. The new Wolverine established an invaluable bridge to prepare local ski jumpers for larger hills in addition to attracting national level competition.

As mentioned, Wolverine had a long reputation of riding like a bigger hill, due to the prevailing northwesterly winds in the Ironwood Township Section 12 valley. The face of the bluff upon which Wolverine sat points directly into that airstream (and did I mention toward the old Savonen homestead?). These natural headwinds were comparable to the next larger hill class. It generates lift for birds, kites, airplanes, and ski jumpers. On sunny days with a gentle breeze, it was not unusual to see a hawk or eagle hovering motionlessly high overhead. After take-off, a ski jumper transitioning into flight position was met by a unique airspeed differential (skier speed + opposing headwind velocity) that produced an exhilarating lift. If still 7 – 10 feet above the landing hill after clearing the knoll, you could peer over the skis to the bottom of the hill slope and outrun. With the lower and more lateral flight trajectory of the updated Wolverine hill design, a ski jumper had to take full advantage of the lift to be successful.

With Wolverine’s reputation for big air and early season lake effect snowfall, it influenced the U.S. national ski jumping team to jump at the opportunity to be the first few to practice and compete on its updated version, prior to the arrival of the regular competitive season.

During the 70’s, the Gogebic Range Ski Club had a nucleus of ski jumpers who maintained the local ski jump(s), trained, and traveled together nearly every weekend to a Midwest tournament from the first week of January through the middle of March. Most jumpers have a favorite hill or two, for various reasons. Perhaps it was the air streams on the hill, the detailed attention that the local club applied to hill preparation, the efficiency of meet registration (on-site in that era), or the ease in traversing the snow paths up the landing hill and scaffold.

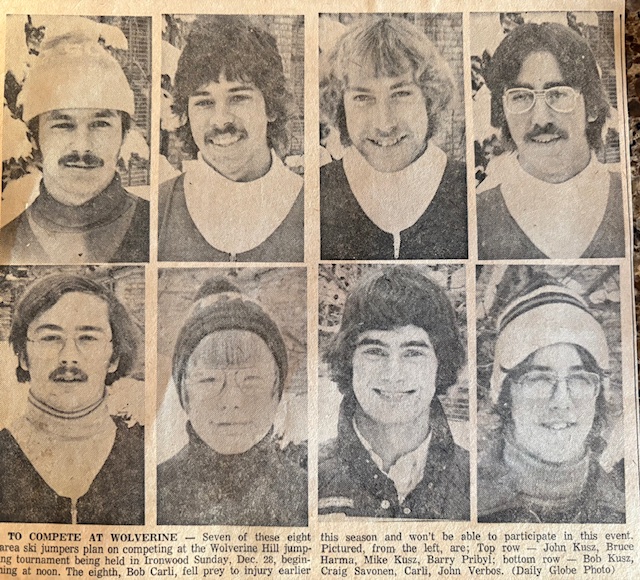

The 1975-1976 season could be characterized as a local ski jumping high point of the 1970’s, accentuated by the inaugural December 1975 tournament. Besides the U.S. national team and other regional riders, the tournament included seven local jumpers (plus one injured jumper), all of which had a family legacy in ski jumping. Five of them were in their last year or two of junior class age. Within the next three years, life’s circumstances dictated that all but John Kusz and I had effectively retired from the sport, and I wouldn’t stay much longer, retiring by 1981.

One of my most memorable rides at Wolverine occurred on one sunny, but otherwise unremarkable Saturday afternoon practice. Only three of us were riding one day, so our small crew alternated between being the jumper at the top of the inrun or standing at the knoll to flag him. As I cleared the knoll during one flight, I immediately sensed a very good ride was in store. Like other sports when an athlete is ‘in the zone’, time pauses and sound nearly ceases. All I could hear was a very gentle tap-tap as my ski tips lightly touched each other a couple of times during flight. And then, after what seemed like a long time, I landed softly as a feather.

An additional benefit of a northwest facing ski hill like Wolverine was that it was mostly shielded from direct winter sunlight. Otherwise, mid-winter thaws could quickly soften and/or melt snow, thus requiring extra effort to keep the inrun snow covered or bring a premature end to the jumping season. The Wolverine inrun and landing were also protected from direct sunlight most of the winter day by trees shading its southwesterly side. (Less favorably, the Copper Peak ski flying hill faces southeast, which increases the challenge of keeping the massive inrun and landing hill prepared with adequate snow covering).

Nevertheless, the first full winter (1976) of new Wolverine tested our stamina for hill preparation due to excess snow. That winter’s snowfall totaled 265 inches, almost 100 inches greater than an average year on the Gogebic Range. As mentioned, although the early arriving and late departing snow in the Ironwood area would theoretically enable the longest jumping seasons in the Midwest (from mid-November until late March), the sheer effort for a small team to keep the hill in ski jumping shape throughout the winter did not afford more jumping time. By then, with the number of active ski jumpers in the Ironwood area dwindled to less than a dozen, it would have been impossible to keep both the Iron Bowl and Wolverine hills in shape. So, without lights on Wolverine at that juncture, jumping practice was limited to weekends. Once the out-of-town ski jumping meet circuit commenced in early January, the number of weekends practicing on the home hill decreased further.

On an intermediate size hill, such as Wolverine, a solid day of practice amounted to anywhere from 8 - 12 rides. On a few rare days, the number of rides exceeded 15. Trudging up the landing hill and inrun would eventually be tiring, even for a young, fit athlete. The total number of jumps that a skier could accumulate over a season varied from club to club. When our ski jumping became mostly limited to weekends during the late 70’s with the migration to the updated, but unlighted Wolverine as our home hill, the total number of jumps that I could accumulate for the entire ski jumping season was in the 175 – 225 range. This total included rides at the out of town meets. In that regard, I envied peers who had home hills with lights and a rope tow or T-bar that facilitated 25 or more rides on a given day. While dealing with less snowfall than Ironwood, some clubs also had a squadron of youth and adults to keep the hill in shape. A hard working jumper in that situation could accumulate more than 400 jumps a year.

By the way, the governing International Ski Federation (FIS) is not favorable to sanctioning an international or ski flying hill meet nowadays if the facilities do not include a lift for the ski jumpers from the bottom of the hill to the top of the scaffold. C’mon, man. The hill climb was part of our cross training! In some international circles, there is even conceptual discussion about creating a fully enclosed tunnel along the entire length of the ski jump inrun. What?!

4.2 – Suicide Hill

A personal milestone in 1977 was riding the largest (70m) jump in the Ishpeming Suicide Hill complex for the first time. Listed at that time as a 70m, equivalent to the smaller of the two standard Olympic hill sizes, it represented a step up in hill size relative to Wolverine. The largest jump in the complex grew in stature from a 70m hill size rating in the 70’s to a 90m rating today. (See Appendix I - Ski Jump Classification for further explanation). Located in a picturesque valley, more recently it has jump sizes classified as 13m, 25m, 40m, 60m, and 90m. It also contained a cross country training center that constituted the U.P. Nordic Ski complex, which over the years has been affiliated with U.S. national ski organizations.

Rich in ski jumping history, the Ishpeming / Negaunee area hosted ski jumping competitions as far back as 1882, which influenced the location of the U.S. National Ski Hall of Fame. Its inaugural tournament was held in 1925 and is one of the few remaining active ski jumps in the U.P. The Ishpeming Suicide Hill is not to be confused with a smaller ski jump in New Boston, Massachusetts also named Suicide Hill that was destroyed by a storm in 1938. Uh huh.

What might be viewed as a culturally insensitive name for the Ishpeming hill was coined in 1926 by a local reporter upon witnessing a skier suffer a non-fatal injury. He defended the name, quoted as saying “Sure, it’s a good hill, but why not have a little color about it.” That attitude reflected the early 1900’s attitude to amplify ski jumping dangers to attract crowds (and readers), before the broader awareness and increased sensitivity to the tragedy of suicide was realized. Nevertheless, the name has stuck to this day.

Suicide Hill was an annual stop for the U.S. national team, who were respected, if not envied, for their flashy uniforms, state of the art equipment, and accomplished coaches. These rock stars of the ski jumping circuit warmed up before the meet by pushing a soccer ball around the outrun, even before the U.S. became a competitive participant in World Cup soccer. They also practiced stationary leaps from the ground into flight position on top of a teammate’s extended arms.

If you could competently ride Suicide, most ski jumps (outside of the ski flying hills) were within reach. As I sat with several Ironwood jumpers having breakfast at a local restaurant before heading out to ride Suicide for the first time, I couldn’t help thinking that the rest of the people in the restaurant were going on with their safe, mundane day, while we would be flying through the air and ignoring risk to life and limb.

At Suicide, you still had to walk up a narrow scaffold while a jumper zoomed down the inrun a few feet away. And, you certainly didn’t want to have so short a jump as to land on the ignominious ‘cowpath’. That was the narrow hard packed trail that forms across the upper knoll where hill personnel and officials regularly crossed to the other side of the landing. Of course, they didn’t traverse the knoll when a jumper was coming!

As compared to other hills, Suicide consistently rewarded distance when a jump was well executed. The curvature of the inrun transition to the take-off table was tighter than most intermediate size hills, imparting more compression when approaching the take-off. Even today, the take-off table is designed with at least one degree more hang (11.5°) than most hills. This feature aligned the flight trajectory well with the 36.5° steep landing table. Headwinds on this larger hill were not greater than that of Wolverine. Spurious gusts were uncommon since the ski jumping complex resided in a natural bowl.

As with any walk in life, one can find humor during incidental, but unique circumstances. At one Suicide Hill meet in the 70’s, the length of the prepared outrun was extraordinarily short and featured a slightly downward slope. Perhaps it was intentionally shortened so a few more paying cars could be squeezed into the surrounding bowl. Despite hill design standards existing for inrun curvature, take-off angle, knoll shape, and landing hill slope (and more refinements introduced since then), the specifications for outrun profile were apparently not so specific at the time.

Jumpers ride through the dip of the steep landing onto the flat outrun with the highest speed of the entire ride. At most hills, there is adequate distance to slow down and ease to a stop with a combination of snowplow or parallel turns. In this case, skiers could not absentmindedly glide to a casual stop. After completing the primary purposes of jumping, flying, and landing, one had to stay alert and initiate a sliding stop immediately after the dip to avoid pounding into the snowbank at the end of the outrun.

During the second day of this meet, the accumulated effect of skiers aggressively skidding to a stop had turned the outrun surface into a sheer ice rink. Among jumpers in queue at the top of the scaffold, we snickered when we witnessed any jumper ahead of us run out of outrun length and crash into the snowbank. It was ski jumping gallows humor at its finest.

Yet, we marveled at one jumper who adopted the unprecedented practice of starting to snowplow brake at high speed while still on the steepest part of the landing. It was a freakish athletic move predating Bo Jackson’s famous horizontal run along an outfield wall in 1990. By the tail end of the meet, the hill management finally placed hay bales at the end of the outrun to cushion skiers with inadequate braking skills or attentiveness.

4.3 – Bulldozer

Bulldozer was a 55m jump carved out of the same ridge as Iron Mountain’s famous 90m Pine Mountain jump. It was uncommon for a hill of Bulldozer’s stature in the upper Midwest to have a mostly natural inrun and landing, but bulldozers accomplished that.

I participated in a two Bulldozer meets, including one in 1977. Without a scaffold, Bulldozer appeared smaller than it was when standing next to its big Pine Mountain brother. It still rode like a larger intermediate sized hill, comparable to Wolverine.

I placed well in the meet, but a small, yet gratifying moment was being noticed by Ed Brisson, the previous head coach of the U.S. national team. A giant in the sport, he was involved in countless aspects of ski jumping for over 80 years (yes, involvement for over 80 years). In addition to being head coach for the Central Division, and later, the U.S. National team, he led numerous advancements in training coaches, hill preparation techniques, and safety.

My interaction with him was brief, but as we know, a lasting impression can happen in an instant. One of the practice days was plagued by crosswind gusts that can disrupt a ski jumper’s flight, to say the least. Naturally hands-on, Coach Ed positioned himself on the knoll that windy day, volunteering as the flagman to signal each jumper to proceed when he sensed that the gusts had temporarily subsided.

On my best practice ride in terms of distance and smoothness, I noticed that I landed on the far right edge of the wide landing, barely a foot or so from the deep snowbank on the side. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but during my next walk up the hill, Coach Ed complimented me for handling the stiff gusts so well, while lightheartedly apologizing for flagging me into it. Since Ed was a born Yooper in Munising (which had its own history of ski jumping until the 1980’s), his personable approach wasn’t surprising.

4.4 – Circus Acts

Early 1900’s ski jumpers persistently encouraged the perception of being bold and daring stuntmen, which they were. It was common for a carnival like setting to attract huge paying audiences. No less famous than P.T. Barnum’s circus incorporated ski jumping into their early venues. A professional ski jumping association actually formed in 1929, but disbanded by 1934, not for lack of demand or paying audience, but due to lack of available, uninjured jumpers.

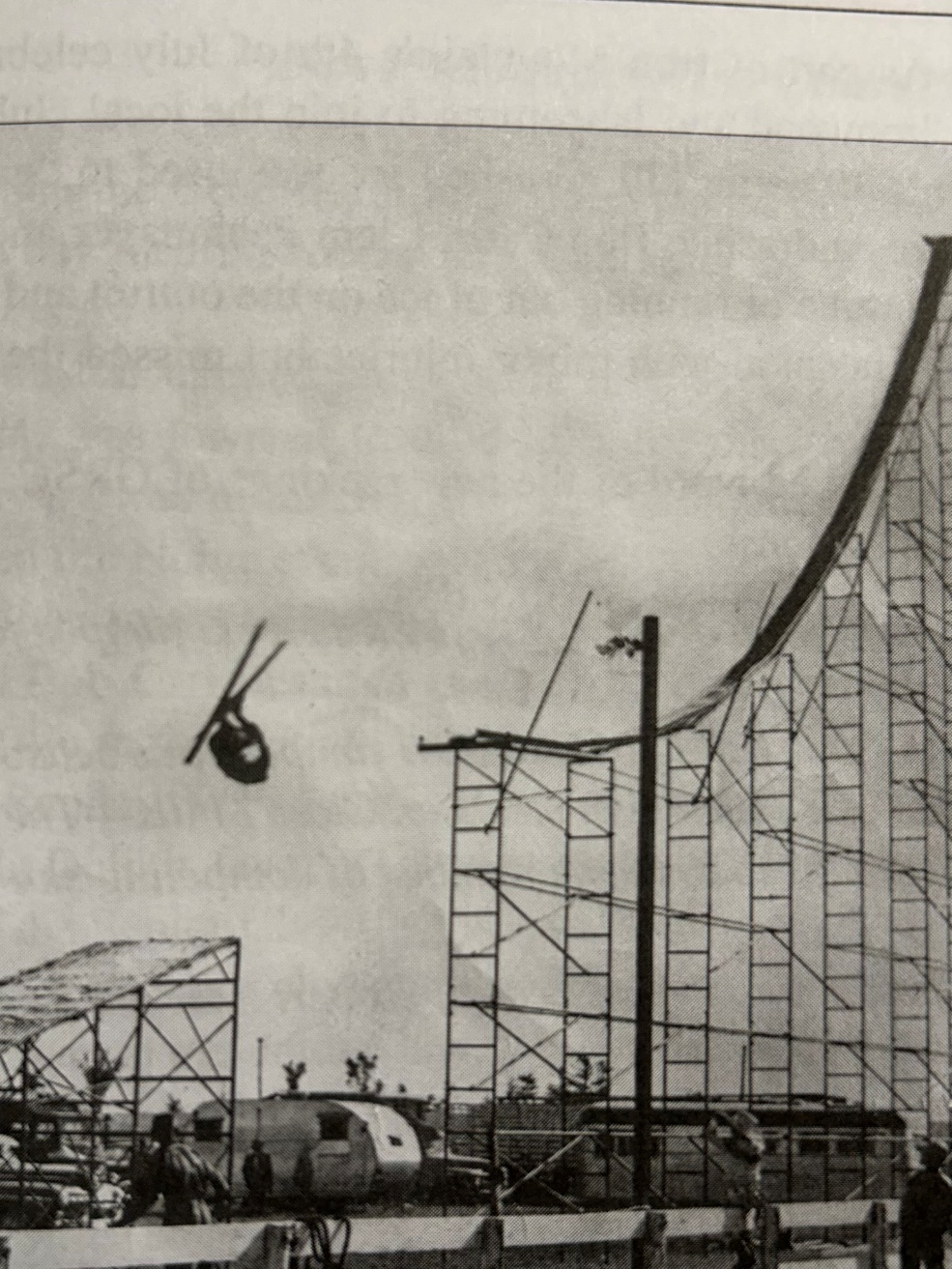

Thrills and spills were promoted as the reason to come and see exhibition riders attempt somersaults and other amazing gymnastic feats with ski equipment and scaffold construction that would astound the most fearless jumper today. To attract audiences, they reinforced the stereotype of a dangerous sport. Pictures of temporary ski jump scaffolds, built exclusively for exhibitions, attest to the laughably flimsy construction that would not pass any safety protocols in today’s litigious society.

Henry Hansen performing his signature somersault in the 1940’s, at some unknown location. He was one of less than a handful that performed this amazing stunt over a hundred times around the country. Fellow ski jumpers called him ‘crazy in the head’. He claimed no serious injuries. Note the rickety super steep temporary scaffold construction with no side rails and at most a 4 foot wide inrun. And he did that with full size, heavy hickory jumping skis.

Even if fear entered a ski exhibitionist’s mind, these macho daredevils of yesteryear couldn’t surrender amidst their ski jumping buddies and responsibilities to the paying public. But, serious apprehension had to be a companion for any sane skier while tiptoeing up a matchstick scaffold. I think they were borderline nuts.

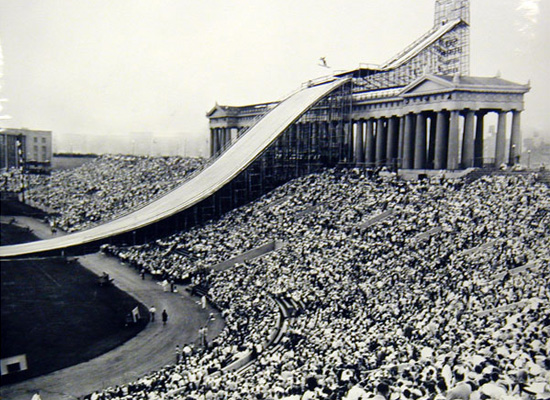

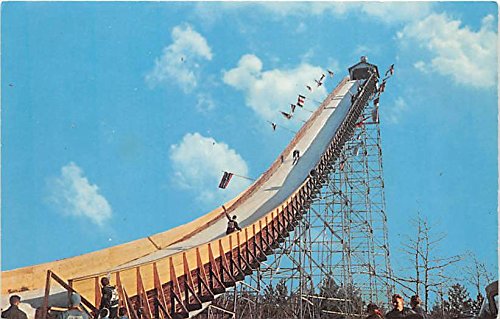

Temporary inrun and landing hill scaffolds for competitive and exhibition jumping were built in large population centers, such as Chicago’s Soldier Field, the Hollywood Bowl, the LA Coliseum, and even a few indoor venues, like New York’s Madison Square Garden. The temporary ski jump constructed at Soldier Field hosted over 60,000 spectators and 140 jumpers. No, the picture is not photoshopped.

In addition to jumping competitions, all types of exhibitions were performed on these hastily constructed jumps. Four ski jumpers from Ironwood contributed to at least one Soldier Field exhibition in the 1930’s by performing the diamond formation. The diamond formation involved four ski jumpers proceeding simultaneously down the inrun and through the air. The formation consisted of a lead skier traveling down the center of the inrun track like usual, followed immediately by two side by side (wingmen) skiers, and trailed by a fourth person.

The potential for mishaps included wingmen coming too close to the inrun walls or colliding with each other. Since both wingmen had one ski riding in rough snow outside of the established inrun track, it would be an uneasy approach to the take-off. Being maybe a foot apart at take-off, the wingmen had to ensure that their ensuing flights did not converge! Of course, if any of the first three riders fell, the fourth and last jumper could be joining a pileup.

One fine day immediately following the conclusion of a Wolverine meet in 1976, someone had the wild hair idea that we should enter carnival mode and recreate the diamond stunt. For our formation, I was nominated as the lead rider which is the easiest job, if you didn’t fall. Before launching down the inrun, my cohorts apprehensively emphasized to me to stay crouched after landing to maintain speed and avoid being caught from behind. I thought “Hey, this is no time to show lack of confidence in your stunt teammate!”

Anyway, away we went. There were no collisions, but since I was the lead rider, I couldn’t see what was transpiring behind me. By the time I had landed and arrived at the outrun to peek behind, I saw a fractured diamond far behind. One wingman had spun out, but the tail rider was able to sidestep him. It wasn’t a professional exhibition and needed more practice and coordination to resemble what local ski jumping stuntmen performed 40 years earlier in Chicago. Our diamond in the rough was fun, but we never tried that again. And to think that the USAF Thunderbird pilots keep four jets within 18 inches of each other in their diamond!

4.5 – Crazy Long

Another more common long-standing tradition in regional ski jumping meets was the long-standing jump. After the formal competition concludes, some tournaments offer jumpers one additional optional ride to compete for long-standing jump honors where distance matters, not style. It is the ski jumping parallel to the King of the Mountain hill climbing award in the Tour de France or baseball’s home run derby. It was not the main event and would only get you a smaller trophy, but it was still something to compete for honorable mention and point of pride. Without concern for preserving style points, a more aggressive go-for-broke approach could be attempted, even though the longest jumps are generally facilitated by maintaining good style.

After completion of the formal meet, many jumpers were likely to forego the long-standing jump competition. They may want to get an early start on a long Sunday evening trip home, especially if they were not in the running for awards from the formal competition. If they had no realistic expectation of cranking out an exceptionally long long-standing jump, it was time to put the skis away. But, with formal tournament tension dissipated, the better jumpers often elected to enjoy one more ‘free’ ride. Pragmatically, the long-standing jump competition also filled time while the official tournament results were being compiled.

Per the name ‘long standing’ and by the usual rules of ski jumping, the jump does not count if one falls or touches snow with any body part. Moreover, if the longest standing jump of the day exceeds the existing hill record, it does not qualify as a new hill record. Only official tournament jumps are applicable.

At the completion of a Wolverine meet one Sunday afternoon in 1980, the organizers staged a long-standing competition. Being an average ‘B’ class senior jumper since graduating from the junior class, it would be unusual for me to compete in the long-standing jump against the U.S. national team and other ‘A’ class riders. However, an unexpected loophole was created, stipulating that long-standing competitors could choose to start from any inrun gate. So, while I had milled around the middle of the senior ‘B’ class pack during formal competition, the free selection of a starting gate presented a unique opportunity.

As I walked past the U.S. team members on my way to the top gate of the scaffold, they were incredulous. Kip Sundgaard, one of the U.S. national team jumpers, peered up from the lower gate he chose for the long standing competition, and blurted “You’re crazy”. I accepted his statement as a badge of courage, insanity, and maybe irritation about unfair rules. Having always used the top gate during practice days at Wolverine and rarely threatening the absolute bottom of the landing hill, I thought nothing of it. Of course, he (or they) could have used the top gate, too, but elite jumpers would have exceeded the safe landing hill distance.

With the additional speed of a well-worn, icy inrun track at the end of a tournament and a good take-off, I catapulted over the knoll higher than ever before. There was acute awareness that this trip was exceeding normal fly zones. When Wally used to say stretch out over your skis and sight the bottom of the hill, I didn’t picture it coming up so quickly to meet me. Unaccustomed to the view, I prematurely backed out of flight position. The result was that I landed much shorter than the initial trajectory offered. By landing far back on my heels, I spun out harmlessly at the bottom.

A top tier jumper accustomed to toying with the extremes of landing hills would have exploited the trajectory, nailing a jump well beyond the hill record (albeit an unofficial distance as mentioned). What a missed opportunity for me! I was disappointed and a bit sheepish about backing out of the flight. But on my walk up the hill afterward, I was saluted by Bob Shea saying “You had so much height you looked like Checko.” Dad used to brag about Chester ‘Checko’ Kusz, brother of Wally, who was a powerfully stocky and exceptional jumper during the heyday of an earlier generation of Ironwood jumpers.

5 - Insights

5.1 – Spotty Training

There was no organized off-season training in the local Gogebic Range ski jumping club in the 70’s. I assumed that other ski jumping clubs with a sizable number of junior and senior jumpers had a comprehensive off-season training regimen. I am sure that was the case for the bigger clubs, especially if mimicking the national team members that were affiliated with those clubs. I would always hear that national team jumpers were wunderkinds of gymnastics and trampolining (as was Wally and some of his peers in previous decades). Foreign to me, it was a cross training activity that developed greater ability for body control while in the air.

Off-season for me meant doing other sports, mostly baseball and basketball. I also weathered a season of high school freshmen football. The most memorable moment was getting hit so hard in a one-on-one blocking drill by the star junior running back that it broke my face mask and left me in a daze. But, I did remember it, so it was memorable! Another attempt at intentional off-season training involved a mediocre sophomore season of cross country running. Later, when about to play a pick-up baseball game with the cross country team and its coach, he snarked “I hope you’re better at baseball than running”. Hah! I did my best to hit a line drive at him. After abandoning those experiments by my junior year, running sprints up the 36° slope of the Wolverine scaffold in the middle of hot summer days seemed like a worthwhile investment.

I credit John Kusz for ingenuity when around 1975 he welded together a unique leg press contraption approaching the size of a Yugo (not quite but) which simulated resistance when lifting out of the inrun position in the vertical and partly forward direction. As a result, I am sure that my leg strength heading into that ski season was as great as ever.